Federal Right-To-Carry Reciprocity falls within Congress’ 14th Amendment powers to protect the Second Amendment and the right to travel.

This feature appears in the February ‘17 issue of NRA America’s 1st Freedom, one of the official journals of the National Rifle Association.

One of the most important issues facing the new Congress will be legislation to protect the safety of interstate travelers so that a person who has a concealed-carry permit at home can lawfully carry in other states. Some people wonder if such federal legislation would violate the letter or spirit of states’ rights. In fact, national Right-to-Carry legislation is solidly within Congress’ 14th Amendment powers to protect the Second Amendment and the right to travel.

After the terrible destruction of the Civil War, it was recognized that reforms were needed to fix the conditions that had led to war. The 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery was the first step, but much more was needed.

First Amendment rights were routinely denied in states that allowed slavery. Anti-slavery books or newspapers had been prohibited. Even books that made no moral argument about slavery, but simply pointed out its economic inefficiency, were outlawed. The free exercise of religion was infringed when ministers were forbidden to criticize slavery from the pulpit.

In 1865-66, the ex-Confederate state governments showed every intention of continuing to abuse civil rights. As the U.S. Supreme Court explained in McDonald v. Chicago (2010), these abuses included new laws prohibiting the freedmen from possessing arms, or requiring them to obtain special licenses. Likewise, their rights to assemble, to work or not work as they chose, and to travel as they wished were banned or constricted.

Congress understood—and the American people agreed—that constitutional reform was necessary so that the federal government would have power to act against state violations of national civil rights.

In 1866, Congress passed the 14th Amendment, and it was ratified by the states in 1868. Section 1 of the 14th Amendment bars state or local government infringement of civil rights, such as those enumerated in the Bill of Rights. McDonald, requiring state and local obedience to the Second Amendment, was part of a long line of cases enforcing Section 1. A few states—including California, New York and New Jersey—refuse to enter into reciprocity agreements with any of their sister states, and they have no provision allowing a non-resident to apply for a carry permit.

While courts can and do enforce the 14th Amendment by holding laws unconstitutional, Congress was given its own, broader enforcement power. Section 5 states: “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” Section 5 is a solid foundation for congressional legislation to protect Second Amendment-protected rights, including the right to carry.

Courts have already explained the scope of Congress’ Section 5 power. For example, Congress may not defy a direct Supreme Court precedent about the scope of a right [City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997)].

At the same time, Congress may go further than the courts have. It may enact measures to protect a right, as long as the measures are “congruent and proportional” to the problem addressed [Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 509 (2004)].

Congress’s powers under Section 5 are not limited to things that the Supreme Court has explicitly declared unconstitutional. For example, although the Supreme Court had ruled that literacy tests for voters, if fairly administered, are not unconstitutional, Congress outlawed literacy tests in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The court upheld the ban. “Legislation which deters or remedies constitutional violations can fall within the sweep of Congress’ enforcement power even if in the process it prohibits conduct which is not itself unconstitutional and intrudes into ‘legislative spheres of autonomy previously reserved to the States’” [Boerne, pages 517-18].

National reciprocity legislation easily fits the Section 5 standards. It is almost perfectly “congruent and proportional” to the problem of interstate travelers being denied their Second Amendment-protected right to bear arms.

In national reciprocity legislation, there is also another important right that is involved—the right to interstate travel. This right is long-established in our Constitution, and the 14th Amendment was enacted with specific intent to give Congress power to protect the right.

The 14th Amendment reads, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” While there is debate about the full scope of these “privileges or immunities,” everyone has always agreed that they include the rights that were created by the formation of a national government. Examples include protection on the high seas, or the right to seek the aid of a U.S. consulate in a foreign nation. These rights are not inherent human rights from natural law; rather, they exist because an American national government was created.

The right to interstate travel is the same. If the 50 states were instead 50 separate nations, there would be no right to travel from Pennsylvania to Vermont via New York. Because we are all citizens of one nation, however, there is a right to interstate travel.

As the Supreme Court said in 1969, “This Court long ago recognized that the nature of our Federal Union and our constitutional concepts of personal liberty unite to require that all citizens be free to travel throughout the length and breadth of our land uninhibited by statutes, rules or regulations which unreasonably burden or restrict this movement” [Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969)]. Or as the court had written a century before, “We are all citizens of the United States, and as members of the same community must have the right to pass and repass through every part of it without interruption, as freely as in our own States” [Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U.S. 35 (1867)].

All of the aforementioned Supreme Court decisions, along with many others on the right to travel, are consistent with the original meaning of the 14th Amendment. When passing the 14th Amendment, Congress addressed a notorious violation of that right.

South Carolina had a law that authorized the capture and enslavement of free black sailors who, when in a South Carolina port, stepped off their ship and onto the land. This was a huge problem for black sailors from states that did not allow slavery such as Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Legislature ordered an investigation of cases in which South Carolina had seized Massachusetts’ free black citizens. The information was intended for a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the South Carolina statute, which was an obvious interference with interstate commerce.

In 1844, the governor of Massachusetts appointed attorney Samuel Hoar to conduct the investigation. Hoar had previously served in the U.S. House of Representatives, and he also had a long career in the Massachusetts Legislature.

When the distinguished attorney arrived in South Carolina, the state Legislature and governor incited mob violence against him. He was forced to flee the state.

The treatment of Hoar was one reason that the 14th Amendment was necessary, according to Sen. John Sherman (R-Ohio). He pointed out that the Constitution had always meant “a man who was recognized as a citizen of one state had the right to go anywhere within the United States.” But “the trouble was in enforcing this constitutional provision. In the celebrated case of Mr. Hoar … This constitutional provision was in effect a dead letter as to him” [Congressional Globe (Dec. 13, 1865)].

Under our Constitution, the general rule is that a U.S. citizen has the “right to be treated as a welcome visitor rather than an unfriendly alien when temporarily present in the second State.” The Constitution bars “discrimination against citizens of other States where there is no substantial reason for the discrimination beyond the mere fact that they are citizens of other States” [Sáenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489 (1999)].For the traveler who has been disarmed by the host state, the only options are to stay shut up in one’s hotel room at night for fear of making a wrong turn down a city block, or to spend all one’s time solely within the confines of a small tourist zone that has a heavy police presence.

Notably, the Supreme Court has affirmed congressional power to enact a statute to thwart private criminal conduct interfering with the right to travel [Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971)].

Another basis for congressional power to enact national reciprocity is the Interstate Commerce Clause, which gives Congress power to act against state or local barriers to interstate commerce. In a famous civil rights case, the Supreme Court held that this power includes the protection of interstate travel.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was shepherded through Congress by pro-gun Sen. Hubert Humphrey (D-Minn.) In Humphrey’s view, “one of the chief guarantees of freedom under any government … is the right of citizens to keep and bear arms” [“Know Your Lawmaker: Hubert Humphrey,” Guns (Feb. 1960)].

After the Civil Rights Act became law, the Supreme Court heard challenges to its constitutionality. One of those challenges involved congressional power to use the Interstate Commerce Clause to protect the right of interstate travel [Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964)].

As the unanimous court explained, the Heart of Atlanta Motel was clearly involved in catering to interstate travel: It was readily accessible to interstate highways 75 and 85 and state highways 23 and 41. Through national advertising, it solicited out-of-state guests. Indeed, 75 percent of its registered guests came from outside Georgia.

Citing many precedents, the Heart of Atlanta court said that the interstate commerce power included the power to protect interstate transportation of persons. Relying particularly on precedents from 1913, 1917 and 1946, the court wrote: “Nor does it make any difference whether the transportation is commercial in character.”

What does all this mean for interstate reciprocity? A few states—including California, New York and New Jersey—refuse to enter into reciprocity agreements with any of their sister states, and they have no provision allowing a non-resident to apply for a carry permit.

These states impose “qualitative” impediments on interstate travel. They discriminate against travelers based on “the mere fact that they are citizens of other States.” They deny the “right to be treated as a welcome visitor rather than an unfriendly alien when temporarily present in the second State.”

As with Hoar, the governments of these states are affirmatively interfering with visitors’ right to travel in safety and security.

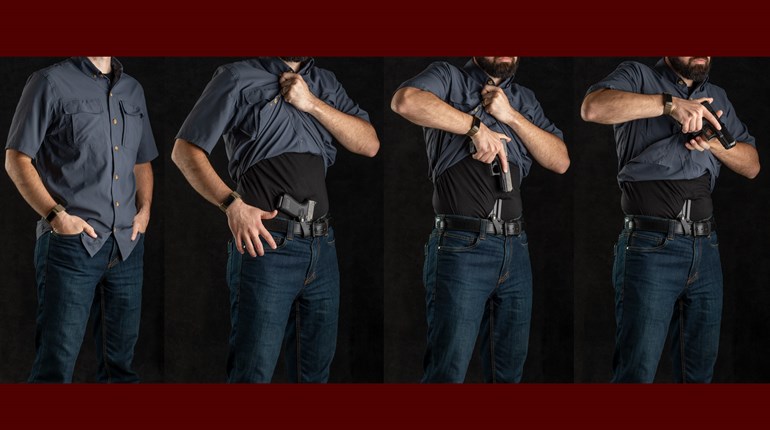

The need to be prepared for self-defense is especially acute when one is traveling in a different state. At home, one will be familiar with the relative safety of different parts of town at different times of the day. A visitor will not have such familiarity, and could more easily end up in a dangerous, high-crime area.

Similarly, a person who goes out for a walk in his or her hometown will know that while there may be several ways to get from point a to point b, one particular route is well-lit, utilizes busy streets, and passes by many businesses that are open at night and in which one could seek refuge in case of trouble. A visitor will not have such detailed knowledge. Almost anyone who has traveled much can remember instances in which he or she unexpectedly ended up someplace that was much more menacing than had been expected.

Further, tourists and similar visitors are targeted by criminals. Their style of dress or mannerisms may indicate that they are not familiar with the area. Because they are not local residents, they are known to be less likely or able to make another trip to testify in court against the criminal, so the criminal has a greater sense of impunity in attacking a visitor. The U.S. Department of Justice has documented the problem [Ronald W. Glensor & Kenneth J. Peak, U.S. Department of Justice, Crimes Against Tourists, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Problem-Oriented Guides for Police, Problem-Specific Guides Series No. 26 (Aug. 2004)].

For the traveler who has been disarmed by the host state, the only options are to stay shut up in one’s hotel room at night for fear of making a wrong turn down a city block, or to spend all one’s time solely within the confines of a small tourist zone that has a heavy police presence.

Yet to be forced to do so is to be deprived of the constitutional right to travel freely and safely throughout the entire U.S. Ensuring that interstate travelers can exercise their Second Amendment-protected right of self-defense is an appropriate subject for congressional action.