While the world certainly breathed a collective sigh of relief with the end of World War II (victory in Europe in May, victory in the Pacific in August), in many other senses, the turmoil was just beginning.

For the U.S. military, the massive demobilization at the end of the war was complete just as new threats emerged and the Iron Curtain took shape. A partial response to this was the formation, in September 1947, of a separate United States Air Force. Virtually all non-aircraft carrier aviation during the war had been carried out by the United States Army Air Corps, but Generals Dwight Eisenhower and Carl Spaatz had already taken steps to prepare for the division of the services before the end of World War II. The emerging role of air power in any future conflict was simply too great to remain part of the landed U.S. Army.

So Michigan-born Iven Carl Kincheloe joined a dynamic, evolving arm of the service in 1949. He was certainly no stranger to aviation. His family supported an early interest in flying, and he was prepared to solo at 14. By the statutory age of 16 (to receive his pilot’s license), he had more than 200 hours of flight time. An aeronautical engineering degree from Purdue University shortly followed. The ROTC cadet was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant and had his Air Force wings by August 1950—just two months after the start of the Korean War.

While Kincheloe was already considered a fine pilot, “fine” and “combat-ready” were two very different things. Instead of heading to Korea, he was assigned to the 62nd Fighter Interceptor squadron and learned to fly the new F-86 Sabre. Despite his young age and relative inexperience, his skills as a pilot became clear, and he was shortly sent to Edwards Air Force Base to help test a new “E” version of the Sabre. In no small way, this was a dream fulfilled: Even if temporarily, he was a test pilot. He would meet and work with some of the premier test pilots of the day, among them Frank K. “Pete” Everest and Chuck Yeager.Despite his young age and relative inexperience, his skills as a pilot became clear, and he was shortly sent to Edwards Air Force Base to help test a new “E” version of the Sabre.

By September 1951, “Kinch” found himself in Korea after all. Before he returned to the United States in May 1952, he would be a captain and rare jet ace with five confirmed victories (five or more air-to-air “kills”; there were only 40 aces total during the Korean War), and many more “probables” and enemy aircraft destroyed on the ground—in itself a relatively uncommon and dangerous feat in Korea.

His return home was to Nellis Air Force Base outside of Las Vegas. There, he chafed somewhat in his assignment as a gunnery instructor. It wasn’t long, however, before the chance to get back into the test pilot role appeared. In early 1954 he went to Britain to attend the Royal Air Force’s Empire Test Pilot School at Farnborough. Returning home in December, in the next four years he would fly nearly every premier prototype of the Air Force inventory: the F-100 “Super Sabre,” F-101 “Voodoo,” F-102 “Delta Dagger,” F-104 “Starfighter,” F-105 “Thunderchief” and F-106 “Delta Dart.”

But the achievements for which Kincheloe was most famed came in the Bell X-2. Of pioneering materials and design, it was a single-seat, throttleable rocket-powered aircraft, carried aloft by a B-50 (postwar modification of the Boeing B-29 “Superfortress”).

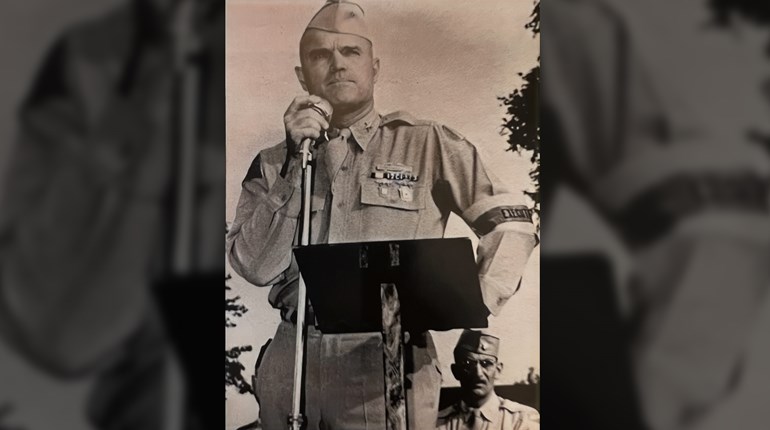

He would eventually fly the X-2 to more than 126,000 feet and 2,000 miles per hour (not quite Mach 3) in September 1956. At the time, 100,000 feet of altitude was considered the end of the atmosphere and the beginning of space, earning the captain the nickname “America’s No. 1 Spaceman,” and winning the Mackay Trophy for his feat. The X-2 program was halted a mere three weeks later when fellow test pilot Capt. Milburn “Mel” Apt was lost along with the aircraft.

Kincheloe would continue in his test pilot role in the “Century Series” fighters, and was selected to be one of the first three X-15 pilots and the “Man in Space Soonest” project. Like so many of the era and profession, Iven Kincheloe is relatively unsung outside aviation circles.

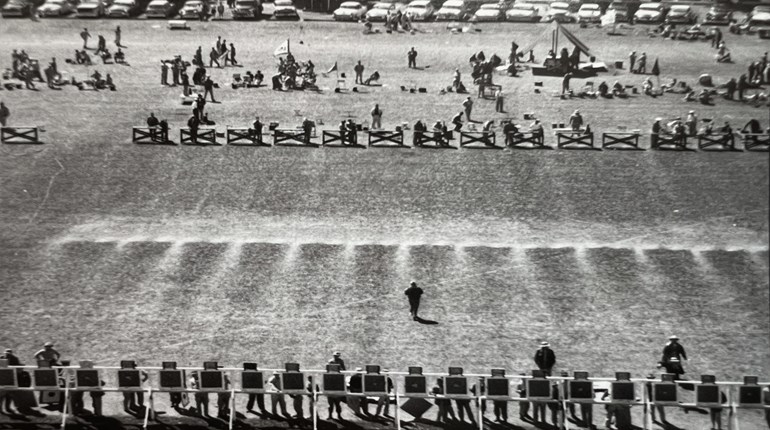

Sadly, disaster would find Kincheloe before the X-15 ever flew. Following Lockheed test pilot Lou Schalk off the runway at Edwards AFB in July of 1958, Kincheloe’s F-104A would lose engine power. Because early Starfighters lacked the “zero-zero” ejection seats of modern fighters, egress from the Lockheed was downward to avoid the aircraft’s high tail. By the time Kincheloe could activate his parachute, his altitude was less than 500 feet. Not quite 57 years ago this month, the United States Air Force lost “America’s No. 1 Spaceman” at the age of 30.

Like so many of the era and profession, Iven Kincheloe is relatively unsung outside aviation circles. But when NRA American Warrior asked noted aviation and period historian Barrett Tillman for a perspective, there certainly wasn’t any hunting around for thoughts.

“Iven Kincheloe made the transition from combat fighter pilot to record-setting test pilot at a time when aviation experienced its most dramatic progress,” Tillman said. “Had he survived, it's likely that he would be far better known to the public, almost certainly as an early astronaut."

For further reading, Mr. Tillman recommends the Kincheloe biography, First of the Spacemen (Duell, Sloan & Pearce) by James Haggerty.