This feature originally appeared in NRA American Warrior magazine, Number 22.

We don’t often get to tell you a story with a timescale or complexity quite like this one. Depending on how you count, the tale could start in 1923, 1951 or any of a dozen other candidate years. Weaving forward, the threads are many.

The first begins during the Cold War with a Department of the Air Force requirement for a high-speed, low-altitude fighter-bomber. Such an aircraft would theoretically streak under enemy radar to pull up sharply, “tossing” a tactical nuclear weapon in a ballistic arc toward Warsaw Pact tank formations on the North German plain or massed in the Fulda/Alsfeld Gap.

Republic Aircraft (later Fairchild Hiller) responded in 1953 with the F-105 Thunderchief. Nicknamed the “Thud” for obscure reasons, the F-105 was a large, powerful fighter-bomber able to handily exceed the speed of sound right on the deck, and even loaded with nearly 15,000 pounds of bombs show “a clean pair of heels” to anything else in the Air Force inventory. This remains an impressive feat, even by today’s standards. Despite initial problems, the Air Force eventually ordered 833, even briefly operating the F-105 in “Thunderbird” flight demonstration team livery.

The F-105 was repurposed to deliver conventional munitions in Vietnam. The "D" model was the workhorse, and could deliver considerably more ordnance than the four piston-engined heavy bombers (like the B-17 “Flying Fortress” or B-24 "Liberator") of World War II fame. The airframe was particularly stable at low altitude, which made it both a good gunnery and bombing platform. In 20,000-plus sorties, the Thunderchief claimed 27.5 air-to-air victories over smaller, nimbler North Vietnamese MIGs, nearly 40 percent of all Vietnam air-to-air kills.

High-speed penetration was crucial in the air war: Russian-provided anti-aircraft technology made the skies over North Vietnam the most heavily defended in any conflict, ever. Correspondingly, losses were heavy: In all, 382 of the planes were lost. In his book Thud Ridge, noted F-105 pilot Col. Jack Broughton said, “The Thud has justified herself, and the name that was originally spoken with a sneer has become one of utmost respect through the air fraternity,” but also that there was “simply no room for error,” especially when operating close to Hanoi.

The F-105 carried out such a large percentage of critical missions into North Vietnam that a mountainous ridge north and west of Hanoi that U.S. pilots hugged to evade air defenses was christened Thud Ridge. Two F-105 pilots were awarded Medals of Honor: Col. Leo K. Thorsness (then captain) and Col. Merlyn H. Dethlefsen (then captain).

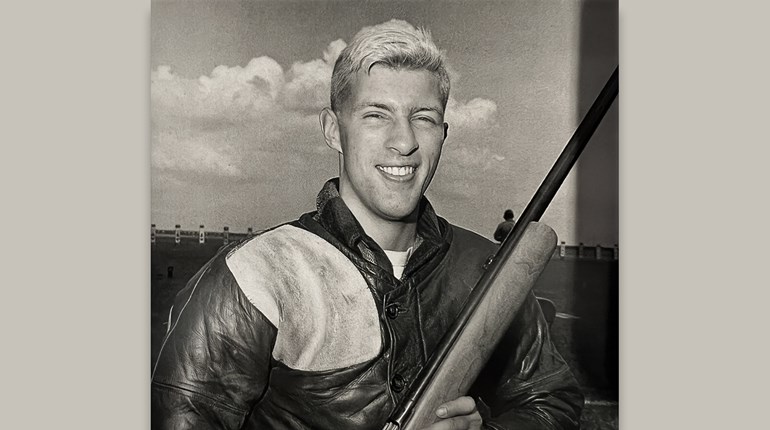

A second thread to our story starts more than four decades earlier. David William Winn was born in Austin, Minn., in 1923. From a young age—4 or 5, as he told it—he knew he wanted to fly. His young life was unremarkable in most other respects, though the Depression brought the Winns many privations: He lost a brother and infant sister to illness, and father John often brought home only IOUs from the hardware firm where he worked. The son of well-educated parents, good schoolwork was a priority. He left home for college in the autumn of 1941.The F-105 carried out such a large percentage of critical missions into North Vietnam that a mountainous ridge north and west of Hanoi that U.S. pilots hugged to evade air defenses was christened “Thud Ridge.”

As it did for so many others, the events of Dec. 7 that year changed many plans. By February 1943, Winn was a new second lieutenant bound for the European theater of operations. Flying out of Sardinia and Italy, he survived 67 missions (mostly in Martin B-26 Marauders and P-38/F-5s) and earned a Distinguished Flying Cross.

First Lt. Winn returned to the United States in late 1944 and was assigned to Williams Army Airfield in Arizona. As part of the Fighter Gunnery Research Squadron at “Willy,” he was a very early jet pilot, flying the Air Corps’ first two operational Lockheed P-80s-the “Shooting Star.” This airplane and the P-51 and P-47 kept him flying for three years after World War II and earned him a regular Air Force commission when it split from the Army to become a separate service in 1947.

But as he would later write: “I could not have chosen, or designed, a life more fulfilling. I made $331 a month and my morale was dangerously high until it finally occurred to me that there must be something in life aside from flying the best airplanes with the best people every day and chasing girls every night. I was 25 when I finally got serious.”

He returned to Minnesota with a Reserve Air Force commission and Air National Guard assignment to finish college, only to be recalled to active duty at the start of the Korean War. Ten years later he returned to finish his Journalism degree, along the way having acquired wife Mary (and two sons) and spending three years in Germany playing, as he called it, “grab-ass with the Russians."

In the relative peace of the following decade, he flew many types of aircraft, but primarily F-86, F-102, F-104 and F-106s all over North American with NORAD. He added the British Hawker Hunter and Electric Lightning while serving on exchange with the Royal Air Force. A stint at the Pentagon and National War College followed, as did a graduate degree in International Affairs.

Now a colonel, Winn watched as loss rates in Vietnam climbed. This led to a decision to request assignment to Southeast Asia. McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, Kan., was briefly home while learning to fly the F-105, and then Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand with the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing. Mary, three sons and a daughter remained behind with family in Minnesota.

The harsh realities of air combat were nothing new to Col. Winn, but found him very personally in April 1968. He was hit by 37 mm anti-aircraft fire near Dong Hoi, North Vietnam. The badly afire but valuable two-seat F model (with a backseat-full of special electronics) couldn't be nursed to Da Nang, and he had to "punch out" over the South China Sea. He was rescued by helicopter.

Ten years later he returned to finish that Journalism degree, along the way having acquired wife Mary (and two sons) and spending three years in Germany playing, as he called it, “grab-ass with the Russians.”Full-fledged disaster, however, waited for Col. Winn’s final (100th) mission. On Aug. 9, 1968, he was hit just as he began his bomb run on an anti-aircraft gun emplacement. He finished his run and again headed for the ocean, but his D was mortally stricken. The comparative safety of the sea proved barely out of reach. Three weeks past his 45th birthday, he became a POW.

Forty days later, he arrived at Hanoi's infamous Hoa Lo Prison (the "Hanoi Hilton"), where the torture and interrogations that had begun on the trek north continued. Twenty-two months of solitary and 55 months of total captivity would follow. His family did not know his fate for nearly three and a half years, and then he was allowed to write them only six times.

As with all senior officers, his Communist captors considered Col. Winn something of a prize. This was an advantage and disadvantage. When his interrogators sought technical information that could endanger other pilots, they were brutally skeptical of his assertion, “This is my second war; I only learn what I need to know to do my job.” When they theorized how valuable a "broken" USAF colonel might be for propaganda purposes, they were also compelled to realize that evidence of essentially unlimited physical coercion could not be disguised. The balance was an incredibly vicious, prolonged and precarious cycle. At least 114 Americans who were known to be captive at one time or another did not emerge during the repatriations of March and April 1973.

Soon-to-be Brigadier Gen. Winn was among the fortunate 591 to return home. He served his country for five more years, and retired from the Air Force in 1978.

In retirement he wrote and spoke a great deal about his Vietnam experiences, and was elected to the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado in 1988. He served as president of that Board from 1992 to 1994. He retired for good then, mostly to read, see the West from the back of a horse and relax with his beloved Mary.

The third thread in our tale arrives in the form of Airman 2nd Class Thomas "Jerry" Jackson. Airman Jackson had already served more than two years in the USAF when he arrived in Thailand in early January 1968 as an F-105 crew chief. He proved—over and over again—that the confidence the Air Force and flight officers placed in him was well deserved. Thunderchiefs entrusted to him were mission-ready for hundreds of successful sorties before he left Tahkli in December.

Jerry left the Air Force in 1970 as a sergeant, but he never forgot the F-105, nor the pilots who flew them. By the spring of 2009, this recollection had festered.

In conjunction with the Haralson County Veteran's Association and association President Sam Robinson, he set out to do something about it. Tallapoosa, Ga., was already the site of a nice Veteran's Memorial, with displays of a U.S. Army Iroquois helicopter (the "Huey" to many), several tracked vehicles and artillery pieces. It seemed like a good fit.

That was the easy part.

It was a year before they found an airframe at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. One of nine, it was part of a Flight Line Security training facility that was no longer in use. All they had to do, said the Air Force, was come and get it.At least 114 Americans who were known to be captive at one time or another did not emerge during the repatriations of March and April 1973.

So beginning in 2010, that's precisely what happened. A small army of volunteers—armed with old tech orders and room and board sponsored by donors—descended on their “bird.” Somewhere along the line, they doubled down: The Air Force offered a second airframe, and HCVA promptly said “yes.”

If that sounds like a big production, it was. But several trips, many donations, a tremendous number of volunteer hours and two years later, both airplanes, albeit in pieces, arrived in Tallapoosa's Helton Howland Memorial Park, courtesy of donated transport from a local trucking company.

Reassembly of the airframes began in February 2013. Once again, Jerry Jackson and the HCVA rallied some remarkable assets to make their vision a reality. With two airframes to work with, they decided to put one on a pylon. Given the site, this seemed an obvious notion as well as a dramatic one (as if the U.S. Army M-60 tank main gun tube pointing practically through your car window wasn’t dramatic enough as you cruise down U.S. Highway 78). But it presented numerous technical problems as, even stripped of engine, armor, armaments and avionics, the airframe still weighs many thousands of pounds.

Suffice it to say that one volunteer engineer, several yards of concrete, donated labor, a steel pylon and one custom bomb bay "mount" later, tail number 61-0127 flew again, slightly more than 30 feet off the ground. It looks ready to pass through your vehicle as you drive by. The second airframe (tail number 62-4292) is on the ground below and behind the pylon-less dramatic from a distance, but what a thrill to be able to walk up and touch it, knowing what it symbolizes.

There's a fourth thread to be considered, though he finds himself in this remarkable story only by profound and grateful accident. As perhaps you've already deduced, I'm that thread: Brig. Gen. Dave Winn was my father, Jerry Jackson his much appreciated crew chief, and 62-4292 their bird.

By the time I joined the story, Jerry Jackson, Sam Robinson and HCVA's work had already borne much of its marvelous fruit. I came on the scene to share undeservedly in a beautiful Independence Day, July 4, 2014, celebration of their incredibly touching and generous efforts to honor Col. Waddell, Cpt. West, Sgts. Wilk and Jackson, and my father.

Unfortunately, we find ourselves living in a time when many won't know how to think about what's been accomplished in Haralson County. It seems like it must be about fame, bravery or victory, and certainly that argument can be made: In some measure those things happened. But something else made them possible, something deeper that is disconnected from self, and perhaps that's the link between the memorial and memorialized:

"Fame is a vapor, popularity an accident, riches take wing. Those who cheer today may curse tomorrow. Only one thing endures—character.” (Horace Greeley 1811-1872)

At least in this corner of Georgia, it takes some to know some.