In an age where coffee—yes, the drink—has an inordinate primacy in American life, it seems all the harder to believe that its predecessor played such a major role in the birth of our nation. Yet the historical record is clear: Considerable tinder was laid to the flame that became the American Revolution over a thing now decidedly un-American in the minds of many—tea.

Two hundred and forty-two years ago this week (Dec. 16, 1773, to be precise) somewhere between 30 and 130 members of the “Sons of Liberty” boarded the Dartmouth, Eleanor and Beaver as they lay at anchor near Griffin’s Wharf (at the foot of Boston’s modern-day Pearl Street), and proceeded to empty their entire cargoes of tea into the waters of Boston Harbor. Some participants famously donned elaborate Mohawk “Indian” costumes to punctuate their strongly anti-British, pro-American sentiments, while others were merely disguised. Such subterfuge was decidedly necessary as many participants were well-known Bostonians (no less than four “Sons” would be eventual signatories to the Declaration of Independence), and their civil disobedience was by no means trivial: The 342 jettisoned chests of tea (roughly 90,000 pounds) had a value of $1.7 million in 2014 dollars.

The tea was largely a symbol, of course, but one of the “long train of abuses and usurpations” that would be immortalized some two and half years later in that same Declaration. But the underlying trouble had been brewing, so to speak, for nearly 80 years.

Popularization of tea among Europeans began nearly a century before with expensive but profitable importation to England and the Continent from China. Entry into England was monopolized by Parliament in 1698 to the benefit of the East India Company, and further legislation sought to prevent any competing importation to British Colonies in 1721. Black markets quickly appeared, primarily favoring the Dutch. Amid mounting losses, East India Company representatives maneuvered Parliament into an increasingly punitive series of taxes reflected in the Stamp Act of 1766 and the Townshend Revenue Act of 1767. The underlying trouble had been brewing, so to speak, for nearly 80 years.

Colonists in the “Americas” responded with protests and boycotts of English tea, while smuggling expanded accordingly. But the finances of the situation were only a part of the equation—much of the revenue the British generated from taxes on tea was used to pay Colonial officials. Many Americans believed these Crown representatives were influential to the point of being oppressive, and indifferent to colonial well-being given that their livelihoods were disconnected from the waxing or waning fortunes of their fellow Americans. More vexing yet, the colonies had no representation in Parliament, and therefore no control over those officials or the policies they enforced. Boston Congregational Pastor Jonathan Mayhew is thought to have coined the phrase in 1750, but by 1765 his notion of, “No taxation without representation,” had become James Otis’, “Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

Americans were not entirely without allies (many from Ireland, who did have Parliamentary representation), and legislation seesawed back and forth through the late 1760s and early ’70s. By the fall of 1773, however, tensions—and tea taxes—were again high, though Boston was the only major colonial port still receiving English tea: In New York, Philadelphia and Charleston, East India Company “consignees” had been convinced not to land their shipments of tea, and thus no taxes were paid.

In the end, simple avarice and nepotism may have brought about the decision of Samuel Adams to turn the Sons of Liberty loose in Boston: Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Hutchinson—with two sons as East India consignees—was determined that the tea on Dartmouth, Eleanor and Beaver should be unloaded. The evening before the Dartmouth would have to leave Boston Harbor or forfeit her cargo due to British port regulations, the “party” started.

British reprisals were swift, and emblematic of an utterly genuine fury: Virtually all parliamentary allies abandoned the colonists. No less than Benjamin Franklin encouraged that the dumped tea be paid for, and full compensation was, in fact, offered by New York merchant Robert Murray and three partners. British Prime Minister Lord North declined. The “Intolerable” and “Coercive” Acts were passed in Parliament with the intention of restoring more complete control of the colonies to England, and met with predictable and equally genuine fury across the Atlantic. Seeing these as clear violations of both English constitutional rights and what in the day were termed “natural” rights, American colonials convened the First Continental Congress in September 1774.British reprisals were swift, and emblematic of an utterly genuine fury: Virtually all parliamentary allies abandoned the colonists.

Moves and counter-moves would follow over the next two years, but no reading of events can leave any doubt that both American colonists and their titular English masters sensed a coming storm. Mollifying moves by both sides were made—Franklin’s suggestion of repayment, for instance, and Parliament’s “Conciliatory Resolution” of February 1775—but to little avail. Tea itself acquired a taint: Samuel Adams’ cousin John Adams and many others considered it unpatriotic and switched to coffee as an “American” hot refreshment.

That same cousin, of course, was the eventual second president of a post-Revolutionary United States, and captured the fervor of the day in his diary entry of Dec. 17: “This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences …” It seems unlikely even he appreciated the full importance.

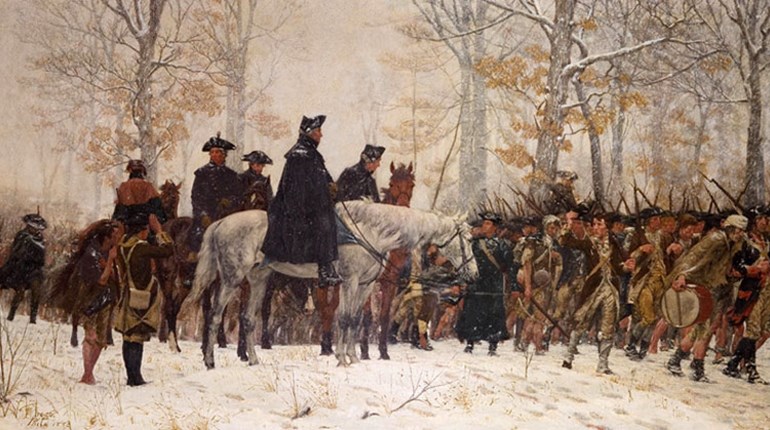

That would wait for April 19, 1775, when 77 militiamen—the first American Warriors to fight on their own behalf—would hold off 700 British Regulars attempting to seize arms and powder stored at Lexington and Concord. As immortalized by Ralph Waldo Emerson in the first stanza of his Concord Hymn (1837), the “shot heard ‘round the world” would irrevocably link the defiantly ruined tea with an independent, freedom-loving spirit, which, it is to be hoped, endures to this day.