This feature appears in the May ‘17 issue of NRA America’s 1st Freedom, one of the official journals of the National Rifle Association.

Staffer’s memoir shows former president’s personal side.

When it comes to public figures, it generally holds that the image is one thing and the individual is something else, and often the two perspectives don’t mesh. Still, there is bound to be some crossover, especially as it pertains to entrenched values or personality traits that shine through no matter how hard the scrutiny of the public eye tries to cover them up.

For generations of Americans who came of age by the 1980s or earlier, Ronald Reagan stands as a shining example of someone who didn’t let being under the watchful eye of the world’s media outlets taint his core values. His respect for America and its way of life, his unbridled optimism and hope, and his gentlemanly manners not only survived, but transcended eight years of being on the global political stage.His respect for America and its way of life, his unbridled optimism and hope, and his gentlemanly manners not only survived, but transcended eight years of being on the global political stage.

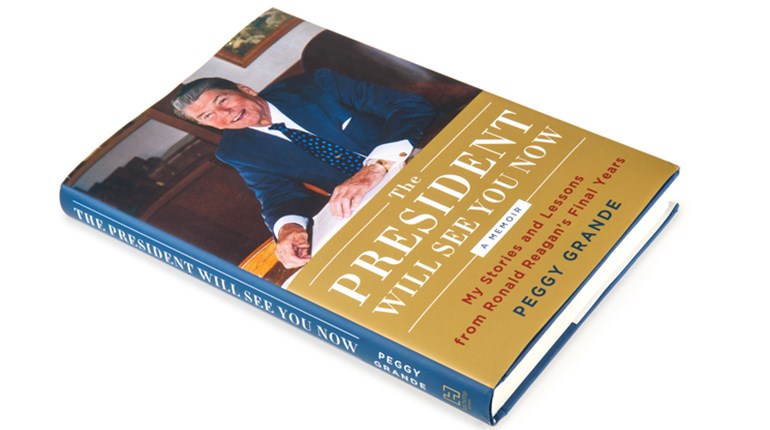

Peggy Grande—who turned an internship at the 40th president’s California office into a full-time job right out of college—spent about a decade working for Reagan in his post-presidency years. The death of Nancy Reagan in 2016 gave her the nudge she needed to write a memoir, The President Will See You Now, in which she reveals a side of the man that proves that Reagan’s penchant for putting the welfare of this nation above all else was more than a passing fancy that he projected in office; it was more like his selfless love of the American way of life and the freedoms we cherish was encoded in his DNA.

Grande relates how she grew up with a love of all things political, specifically things related to the presidency and the men who have held that office. So the chance to work for Reagan’s office was a dream come true for a California-raised political history buff.

As she reflects on her impressions of Reagan, she shares how she, too, realized that the real person often is a departure from the larger-than-life image someone holds of him. “Ronald Reagan was one of the few who did not seem smaller than his image, which was enormous to most. He was even more charming, more handsome, and more gracious than imagined. He was a man who genuinely delighted in meeting new people and had a way of making everyone feel as though they were important to him—because they were,” she writes.

Whether relating the story of how he interacted with an autistic boy who seemed to know more about Reagan than the former president himself did, or his meeting with an elderly Romanian woman who dropped to her knees and bowed to the floor beneath him in an expression of gratitude for his work in getting people in the former Eastern Bloc countries a taste of freedom, Grande paints a picture of Reagan’s private self that, indeed, lives up to the image he conveyed.

“In all those meetings there was a common thread,” Grande writes. “One life, the president’s, had made an overwhelming, positive impact and had changed the course of each of their lives forever.” Through lively descriptions capturing his interactions with people … the reader sees evidentiary cases of the man’s down-home style and unflagging faith in mankind, along with his undying optimism that humanity must strive for something better.

Her narrative takes readers on a behind-the-scenes look at the daily life of a former president, a masterfully woven account in which, through skillful use of vignettes, she peels back the layers of Reagan’s persona to reveal—without having to come right out and say it—the depth of the man’s honor and integrity.

Grande peppers her chronology of 10 years as a Reagan staffer with a mix of anecdotes about life lessons learned and examples of “Reagan the raconteur.” But more importantly, through lively descriptions capturing his interactions with people—from the average person on the street to those who were his contemporaries on the world stage—the reader sees evidentiary cases of the man’s down-home style and unflagging faith in mankind, along with his undying optimism that humanity must strive for something better.

It was his gift as a storyteller that served as a telltale sign for Grande that something might be wrong with Reagan. In the mid-90s, she tells of how he’d sometimes get lost in recounting his exploits to visitors—tales she knew well from having heard them before. And it was after a couple of instances of his faltering when he regaled his guests that she first suspected he might have a problem. It was a few short months later that he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Grande does an admirable job, without getting overly maudlin, of capturing the struggles the Reagans and the staff went through as they came to grips with the toll the disease took.

The President Will See You Now is well structured, bookended by recounts of two deaths, Nancy Reagan’s and the role it played in Grande’s decision to publish the book, and recollection of the former president’s state funeral. The author closes with a salient lesson learned from Reagan’s stewardship of this nation: “We don’t just need that one man, Ronald Reagan, now again in America. We need everyone who was blessed and touched by that one man to bring his legacy in their lives back to their families, their workplace, their community, and the world.”

The President Will See You Now, $28, Hachette Books.

L.A. Luebbert is managing editor for the print edition of America’s 1st Freedom.