The Medal of Honor occupies a well-known position in American culture: Relatively few would not know it as the highest decoration for valor in a military context. The extent of bravery and self-sacrifice implicit in the award is sobering—more than 60 percent are awarded posthumously. Roughly 50 million Americans have worn their country’s uniform, but only 3,496 have received the Medal, and only 77 recipients are alive today.

Perhaps more surprising still, with three very limited exceptions, it was long the nation’s only medal recognizing heroism or gallantry “above and beyond.” In a technical sense, the Purple Heart is older (its predecessor dating to 1780), and many United States wars were fought without any other decorations. In part, this stemmed from the desire of many early, senior American military officers not to emulate European militaries and their relatively profligate decorations. Simply, it smacked of aristocracy—perhaps the most singular thing the Founders sought to avoid in almost every facet of a “new” American life and culture.

General-in-Chief of the Army Winfield Scott was a powerful resister of the notion of individual decorations, but his retirement in 1861 cleared the way for both a Navy “Medal of Valor” (signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in December 1861) and Army “Medal of Honor” (July 1862). A total of 1,522 were awarded by the end of the Civil War, including four double awards (of only 19 total), one to civilian female surgeon Mary Walker (one of only eight women) and 25 to African-American soldiers and sailors.

After the war, a huge number of Easterners moved west by railroad and prairie schooner, resulting in one of the most diverse periods of award. Inevitably, westward migration brought increasing conflict with Native Americans, and long series of skirmishes alternated between failed treaties and open warfare. (West of the Mississippi, the “Indian Wars” spanned 95 years—1823 to 1918). Many Civil War troops were sent west to protect settlers of every stripe. Between 1858 and 1886, perhaps the most famous nemesis of both Mexican and American expansion was Apache Chief Geronimo.

Union Major General George Crook was reduced to his permanent rank (Major) at war’s end, and sent west like many other officers. He became one of the most capable Indian fighters and negotiators, pacifying the Snake and Paiute tribes in Oregon before being assigned to the Arizona Territory by President Ulysses S. Grant. As he rose again through the ranks, Crook also became well known for his ability to recruit Native Americans as scouts and emissaries, believing as he did that “the wilder the Apache was, the more likely he was to know the wiles and stratagems of those still out in the mountains.”He later became an advisor to Indian agents throughout the West and, eventually, to three U.S. presidents (Cleveland in 1887, Roosevelt in 1909 and Harding in 1921) on Indian affairs.

One of his recruits heading into the Winter Campaign of 1872-73 was 19-year-old William Alchesay, a White Mountain Apache. The goal of the campaign was to convince the Chiricahua Apache to stop their raiding and surrender peacefully, and Alchesay was one of Crook’s primary envoys to Geronimo. From December through March, pursuit was mingled with negotiation and battle (Salt River Canyon and Turret Peak), and eventually most of the Apache warriors and their families surrendered at Camp Verde, Ariz. General Crook’s aid and fellow Medal of Honor winner Captain John G. Bourke described Sergeant Alchesay as “a perfect Adonis in figure, a mass of muscle and sinew of wonderful courage and great sagacity, and as faithful as a Irish hound.”

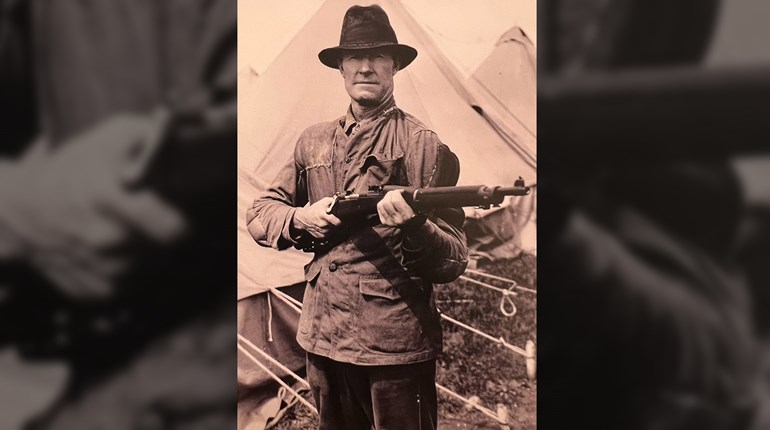

Alchesay would serve under General Crook again (1883 through the end of the Apache Wars in 1886). He later became an advisor to Indian agents throughout the west and, eventually, to three U.S. presidents (Cleveland in 1887, Roosevelt in 1909 and Harding in 1921) on Indian affairs. Also a successful rancher, farmer and family man, he served his people as chief of the White Mountain Apache until 1925.

It is the unfortunate case that many early Medal of Honor citations, like Alchesay’s, are sparse, saying only “gallant conduct during campaigns and engagements with Apaches.” In fact, he was just one of 10 Indian Scouts cited by General Crook.

A careful reading of his life and circumstances, however, give a much fuller measure of the man. William Alchesay was not merely a prototypical, effective soldier of an enduring type—Indian Scouts continued on in the U.S. Army until the 1940s, when many of their traditions became those of early U.S. Special Forces—but also one who found meaning and purpose in life after warfare. Among his many other achievements, he cultivated and maintained a close friendship with Geronimo for the remainder of his life.