The lever-action rifle didn’t just change the West. The 16-shot Henry rifle (shown here), and other modern arms, were also used by newly freed Blacks in the late 19th century to defend their freedom.

When looking at the struggle of Black people in the United States for their natural rights—those of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness—the right to bear arms, and particularly those arms employing multi-shot technology, has been vital.

Opponents of the AR-15, America’s most-popular rifle, argue that its repeating capability is exceptional and that such a thing was not contemplated by the framers and ratifiers of the constitutional right to arms.

This is false.

Many versions of repeating firearms were available at the time of the framing. But the most-vivid demonstration that the right to arms was embraced with full appreciation for the capabilities of repeating firearms is the transformative post-civil war extension of federal constitutional rights as limitations on states through the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868.

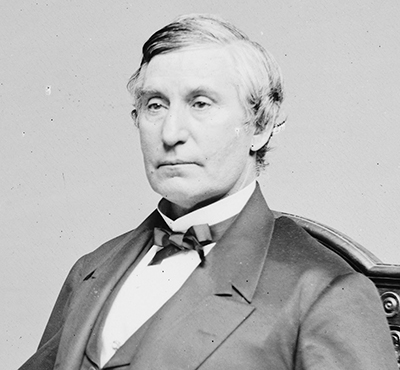

The views of the drafters and advocates of the Fourteenth Amendment are plain. Sen. Jacob Howard of Michigan introduced the proposal by explaining that “the great object” of the amendment is to “restrain the power of the states and compel them in all times to respect these great fundamental guarantees … secured by the first eight amendments of the Constitution; such as the right to keep and bear arms.”

The same congress that advanced the Fourteenth Amendment also abolished southern state militias, demonstrating a vision of the right to arms as an individual right, and not merely some federal protection of state prerogatives.

By 1868, the capabilities of repeating rifles were widely understood. In 1861, B. Tyler Henry’s 16-shot, lever-action rifle already had powerful advocates in the Union Army. The Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton; Secretary of Navy, Gideon Welles; and President Abraham Lincoln all received gifts of presentation-grade Henry rifles. In May of 1862, the Henry was tested at the Washington Navy Yard, where one 15-shot magazine was fired in 10.8 seconds. A total of 1,040 shots were fired with hits made out to 348 feet on an 18-inch square target. This was done with .44-caliber cartridges firing 216-grain bullets.

Commentary from the period highlights the acknowledged utility of the lever-action repeater in the context of civil unrest. In July 1862, George Prentice, editor of the Louisville Journal, said, “In these days when rebel outlaws and raids are becoming common in Kentucky. … Certainly the most effective weapon that could be used with the most tremendous results is the one that we have mentioned recently on two or three occasions, the newly invented rifle of Henry.” Prentice ultimately bought several hundred Henry rifles and resold them to loyal Union men.

After the war, the utility of the repeating rifle was abundantly clear to Black people who plainly needed more than the parchment barriers of the Fourteenth Amendment to protect them against both private terrorism and the overtly hostile state and local governments.

The Black Codes of this era (local and state laws that aimed to reinstitute slavery in a different form) reflected the age-old wisdom that subjugation requires disarmament. The Freedmen appreciated instinctively that arms were vital to their survival. They defied local and state disarmament efforts and defended their neighbors, friends and selves. We know from newspapers of the day, petitions to Congress, and reporting of Freedman’s Bureau agents that the right to arms was a paramount concern for those newly freed in the territory where they were recently enslaved.

By the end of the 19th century, the importance of repeating rifles to Black people was so well-established that storied anti-lynching advocate, Ida B. Wells, would declare, “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every Black home.”

Wells’ praise of the Winchester was not empty rhetoric, and her perspective was not just historical. She was referencing two recent episodes, one in Jacksonville, Fla., and one in Paducah, Ky., where well-armed Black people thwarted lynch mobs.

Wells drew similar lessons from Black people using repeating technology in self-defense in Oklahoma. Seven months before she arrived, Black men wielding Winchester rifles defied a mob to rescue Edwin McCabe, the Black founder of Langston, Okla., who had the grand vision of becoming governor. After mobs in Memphis had lynched her best friend and sacked her newspaper, Wells traveled there in search of a more hospitable environment where she might recommend Black people to migrate.

Wells’ exhortation was heeded by countless men and women who faced petty tyranny and mobs during the first century of Black citizenship in America. And hers was not an isolated voice. The commitment to armed self-defense and the deployment of multi-shot and multi-projectile firearms was common from the leadership to the grassroots.

After the 1906 Atlanta race riot, W.E.B. Du Bois described buying a Winchester shotgun “and two dozen rounds of shells filled with buckshot,” as defense against roving mobs. Du Bois’ future compatriot at the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), Walter White, was only a boy at the time of the Atlanta riot, but he vividly recounted crouching with his father in a darkened parlor, clutching a rifle as a mob descended on his Atlanta neighborhood.

Du Bois and White pulled heavy oars at the burgeoning NAACP. Du Bois was the intellectual force behind the organization’s flagship Crisis magazine. White would lead the NAACP for more than two decades, into the 1950s. So, it is not surprising that the NAACP cut its teeth as an organization defending Black people who had used guns to defend themselves against mobs and majoritarian tyranny.

The first major litigation supported by the NAACP was the 1910 self-defense case of Pink Franklin. Franklin’s troubles stemmed from his quest for better wages. He had agreed to work for a planter, but then quit to take a better job. This sort of thing is common practice today and was equally common then, at least for white people. But in 1910, for Black sharecroppers like Pink Franklin, the pursuit of better pay was restricted by a special category of agricultural contract governed by the South Carolina Criminal Code. The law was basically a renewed version of the Black Codes that the defeated Confederates attempted to enforce against freedmen immediately after the Civil War. The law said that sharecroppers who broke labor agreements with planters could be fined and jailed. Black contract-breakers who could not pay their fines, or their growing fees from incarceration, could then be sold off into the convict labor system, virtually slaves again.

After Franklin left his first boss for better pay at another farm, the jilted employer swore out a warrant for his arrest. One dark morning around 3 a.m., government men descended on Franklin’s shanty. Stories disagree on the details, but, basically, Franklin said he was surprised in the dark by strange men in his bedroom. Franklin said when one of them fired at him, he rolled to the repeating rifle he kept in the corner and came up shooting. A surviving constable, however, claimed that the doors to Franklin’s house and bedroom were ajar; that they entered and were attacked by Franklin. There was agreement on the fact that Franklin shot two constables, one of them fatally.

Pink Franklin was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. The NAACP supported Franklin’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court and lobbied the governor to commute his sentence. The advocacy and lobbying continued for nearly a decade, and Franklin was finally released in 1919.

During the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, repeating firearms helped Black activists survive. In Carroll County, Miss., activist Leola Blackmon repelled Klansmen who set a cross on fire in her yard. “That night when they set that cross afire at my house … I thought to cut them down, but I didn’t. I just let some bullets through behind them. I had a rifle. It would shoot 16 times. And I just lit out up there and starting shooting.”

One county over from Blackmon, activist Hartman Turnbow staunched a firebomb attack on his home by deploying his 16-shot semi-automatic rifle. The next morning, the license plate of the local sheriff was found in Turnbow’s driveway.

Turnbow also appreciated that the capabilities of his semi-automatic rifle were rivaled, and maybe exceeded, by another common firearm, the shotgun. Turnbow described his calculation this way: “The next year when they shot over here, I had got an automatic shotgun, Remington 12-gauge, and them high-velocity buckshot. So I jumped up and run out and turned it loose.” (In 1997, the U.S. Joint Service Combat Shotgun Report confirmed that, within 40 yards, a shotgun loaded with buckshot can be superior to many repeating rifles, a conclusion that clearly would have been no surprise to Turnbow.)

In Bogalusa, La., in 1965, Robert Hicks, one of the early leaders of the Deacons for Defense, repelled terrorists who attacked his home using a modern copy of the Winchester rifle Wells had extolled nearly a century earlier. In Birmingham, Ala., legendary activist the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth was protected by armed “Civil Rights Guards” after suffering several violent attacks. Shuttlesworth’s colleague, The Rev. Ed Gardner would later describe how they survived those times with the aid of his “non-violent Winchester.”

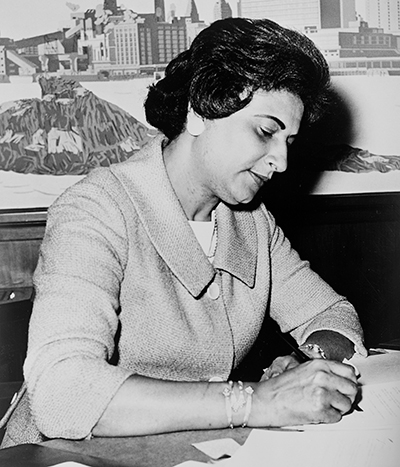

When Thurgood Marshall and his young assistant, future federal court judge, Constance Baker Motley, were litigating school desegregation cases for the NAACP, they, too, were guarded by armed men.

Judge Motley described one episode this way: “While in Birmingham … we stayed in Arthur Shores’ spacious new home on the city’s outskirts. This house had been bombed on several occasions, but because we could not stay in a hotel or motel in Birmingham, we had to take up Shores’ offer of his bomb-prone abode. … When Thurgood and I arrived, the garage door was wide open. Inside were six or eight Black men with shotguns and machine guns who had been guarding the house since the last bombing. … When we went to court the next day, the driver of our car and one other man in the front passenger seat carried guns in their pockets.”

Daisy Bates, who shepherded the Little Rock Nine through the turmoil of desegregation efforts in Arkansas, wrote about taking her turn in the armed watch of her home, wielding a venerable semi-automatic .45-caliber 1911 pistol. One night she shot multiple rounds to repel a man who had thrown a flaming missile at her home and was about to launch another. He had the good sense to retreat, and Bates survived to carry on the fight.

Throughout the South, the Deacons for Defense and Justice would protect activists in a variety of contexts. In 1966, Martin Luther King, Jr. and others gathered to support a wounded James Meredith and to continue his “Mississippi March Against Fear.” The discussion about whether to use the Deacons as security illuminates the worry within the leadership that legitimate self-defense might spill over into political violence, which the non-violent movement dearly hoped to avoid. As movement leaders gathered in Memphis, a vanload of Deacons pulled up and got out. Some of them were carrying semi-automatic M-1 Garand rifles (the WWII infantry rifle that Gen. George Patton called “the greatest battle implement ever devised” and which the United States government has sold to the public for decades through the Civilian Marksmanship Program).

Representatives of the NAACP and the Urban League thought it was too much of a risk to have the Deacons at the March. King ultimately sided with the leaders of the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee to welcome the Deacons. Although they would not take a visible role in the march, armed Deacons remained close, surveying the route and guarding campsites. A subsequent interview with Deacon Charles Sims indicates that, in addition to M1 Garands, Deacons also were armed with M1 carbines. Sims said, “I was carrying two snub-nosed .38s … and had three men riding down the highway with semiautomatic carbines with 30 rounds apiece.”

In this case, resistance to tyranny did not mean fighting and winning a war. There were no tea-tax vandals, salty minutemen or pamphleteers urging a breakaway from the mother country. But this fight was against tyranny in its ultimate and most-vicious iteration, against imminent threats to life and limb from forces small and large. This story of resistance is filled with authentic American heroes, using the tools of self-defense wisely incorporated into the framing documents of this country, and with lessons we should never forget.

Nicholas Johnson is Professor of Law at Fordham Law School. He is the author of Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms (Prometheus 2014) and numerous articles on firearms law and policy.