Gun owners have made undeniable progress in shifting public opinion away from bans on the firearms gun-control advocates hate.

Consider, in 1959, Gallup asked the public, “Do you think there should or should not be a law that would ban the possession of pistols and revolvers, except by the police and other authorized persons?” Sixty percent of respondents answered, “Yes, there should be.” Gallup has continued to ask a similar question ever since. In 2021, with 42 states that recognize the right to carry a handgun outside the home for self-defense (21 without obtaining prior government permission), only 19% of Americans supported a total civilian handgun ban.

By the 1990s, anti-gun activists understood that their dreams of a federal handgun ban were slipping away. Deliberately playing off of the general public’s ignorance, as admitted by Violence Policy Center’s Josh Sugarmann, gun controllers shifted their primary focus to prohibiting certain types of commonly owned semi-automatic firearms that they maliciously designated “assault weapons.”

The strategy seemingly enjoyed some early success. A handful of states enacted bans on the targeted firearms, and, in 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Federal Assault Weapons Ban. At the time, CNN/USA Today polling showed that 71% of Americans supported a ban on “certain semi-automatic guns known as assault rifles.”

In the decade that followed, the Clinton ban proved an abject failure, with multiple Department of Justice-funded studies unable to show that the measure had reduced crime. Presented with this inefficacy, the ban was allowed to sunset in 2004.

Gallup regularly asks Americans, “Are you for or against a law which would make it illegal to manufacture, sell or possess semi-automatic guns known as assault rifles?” In the six times Gallup has asked the question since 2004, there has never been majority support for such a law.

This marked shift in public opinion around gun bans, while encouraging, doesn’t mean our opponents have given up on these unpopular policies. Recall that the 2020 Democrat presidential primary devolved into a game of gun-control one-upmanship, wherein now-President Joe Biden and now-Vice President Kamala Harris endorsed confiscatory gun bans. Americans should take Biden and Harris at their word when they say that they would ban and confiscate firearms given the opportunity.

However, the decreasing popularity of gun bans does shift the political calculus in the near term and gun controllers have gotten wise to this fact. That’s why gun-control advocates are increasingly advancing policies that target gun owners, rather than the tools of self-defense.

Such measures can be much more complicated than gun bans and often don’t elicit the same reaction as a politician saying they are going to take your property. In fact, gun- control advocates carefully craft their messaging on these controls to engender sympathy from those who might have only a superficial understanding of their policies. After all, we as law-abiding Americans all want to tackle and take seriously issues like domestic violence and mental illness, but throwing bedrock American ideals of due process out the window should not be the answer.

Chief among the efforts aimed at gun owners is the campaign to expand the federal and state categories of persons prohibited from possessing firearms altogether.

This campaign serves gun-control advocates in two ways. First, wider prohibited-persons categories mean that fewer Americans are able to exercise their Second Amendment rights. As gun controllers view any exercise of the Second Amendment right as detestable, any curtailment of this activity is a positive in their minds. Second, limiting the potential universe of gun owners has profound political ramifications. Those barred from gun ownership are less likely to invest themselves in the issue and engage in the pro-gun activism and voting necessary to preserve the Second Amendment right. Therefore, expansions of the prohibited-persons categories have something of a compounding effect, where each extension of the categories makes further expansions and other gun controls more achievable.

The most common avenues are attempts to expand the existing federal, and state equivalent, possession prohibitions for anyone “who has been convicted in any court of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.” All prohibitions based on misdemeanor convictions are problematic. Misdemeanor defendants often aren’t entitled to the same array of due-process protections afforded felony defendants. Moreover, as such prohibitions have been deemed “collateral consequences” rather than punishments, newly enacted prohibitions can be triggered by old convictions where the threat of a firearm prohibition was never in play at the time an individual accepted a plea deal. Gun-control advocates have calculated that the stigma surrounding anything labelled “domestic violence” is enough to override traditional civil-liberty concerns.

At present, the federal prohibition applies to a person with a conviction for an offense that “has, as an element, the use or attempted use of physical force, or the threatened use of a deadly weapon, committed by a current or former spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim, by a person with whom the victim shares a child in common, by a person who is cohabiting with or has cohabited with the victim as a spouse, parent, or guardian, or by a person similarly situated to a spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim.”

Marketed at the time of enactment as a firearm prohibition for serial violent domestic abusers whose victims were too scared or reliant upon their abuser to assist in securing a felony conviction, gun-control advocates have successfully encouraged the federal courts to read the “violence” component of “crime of domestic violence” right out of the law. In U.S. v. Castleman (2014), the U.S. Supreme Court determined that a person’s use of physical force need not be violent in order to trigger the firearm prohibition. Rather, such physical contact may consist of only the slightest “offensive touching” necessary for common-law battery. Far from requiring the type of violence contemplated at enactment, a person can now lose their gun rights for something as minor as grabbing a spouse or other relation’s arm as they walk away. In fact, under the common-law battery standard, merely touching a person’s clothing, bag or something they are holding in their hand in a completely non-violent manner could give rise to a prohibiting conviction.

Having successfully removed the “violence” component from the federal “domestic-violence” prohibitor, gun controllers set to work on removing the “domestic” component. The current version of the federal Violence Against Women Act (H.R. 1620 or VAWA) would alter the types of relationships that give rise to a prohibiting “domestic violence” conviction to include “dating partners.” There is no temporal or cohabitation limit to the definition of “dating partners.” Ladies, next time you see that cad who ghosted you after two dates, don’t throw a drink in his face—it might cost you your gun rights under the federal government’s increasingly ridiculous definition of “domestic violence.”

States often have similar, but distinct “domestic violence” firearm prohibitions under state law. Each year, NRA-ILA’s state directors and attorneys confront a host of efforts to expand state prohibitions well beyond even what the U.S. Congress is considering in VAWA.

Another federal prohibited-person category gun controllers have deemed rife for abuse concerns those suffering from mental illness. Federal law prohibits firearm possession by anyone “who has been adjudicated as a mental defective or who has been committed to a mental institution.” The anti-gun activists and the federal administrative state have targeted both halves of this category for expansion.

In an effort to prohibit as many people as possible from possessing firearms, the federal government has willfully misinterpreted “adjudicated as a mental defective.” For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs labels those assigned a fiduciary to handle their VA benefits as “mental defectives” for the purposes of the firearm prohibition. Thanks to this outrageous administrative expansion of a prohibited-persons category, veterans who might need a little help balancing their checkbook are dumped into the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) alongside the likes of violent felons, the dishonorably discharged and those who have renounced their citizenship.

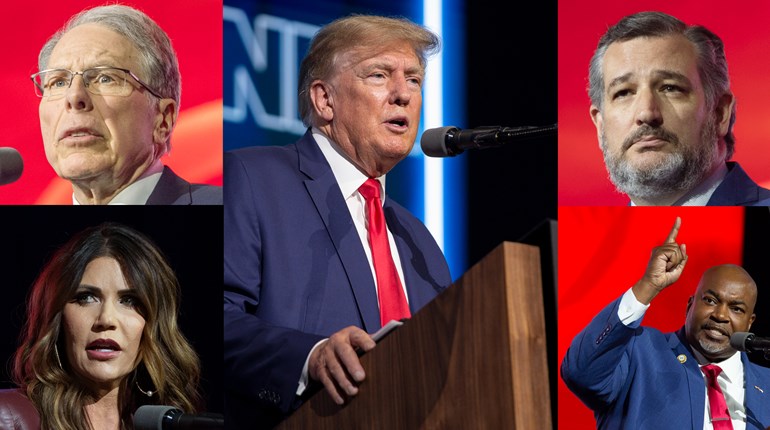

In its last days, the Barack Obama administration attempted to expand this practice to Social Security beneficiaries receiving benefits for a mental-health disability who had been assigned a representative payee to manage their entitlement. Thankfully, the 115th Congress and President Donald Trump nixed the change upon taking office.

Concerning the definition of “committed to a mental institution,” again, anti-gun forces in the administrative state have attempted to expand the definition well beyond the type of formal institutionalization Congress envisioned when it enacted the prohibition in 1968. In 2014, ATF published a notice of proposed rulemaking (Rule 51P) to alter the “committed to a mental institution” definition in the federal regulations to include involuntary outpatient treatment. As NRA-ILA noted at the time, the expanded definition could implicate the type of “mandatory court-ordered counseling or treatment … common in a wide range of legal proceedings, from custody disputes to diversionary dispositions for relatively minor and non-violent criminal offenses such as simple possession of marijuana or driving while under the influence.”

Of course, none of these federal efforts go anywhere near far enough for the professional gun-control advocates. The Michael Bloomberg-bankrolled Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health advocates a host of new prohibited-persons categories. These include a 15-year prohibition for persons convicted of any “violent misdemeanor,” no matter how minor. The Bloomberg front group also advocates a prohibition on “persons determined by a judge to be a gang member.” Aside from being a violation of the First Amendment freedom of association, the policy would eschew traditional due-process protections for the whims of a single judge. Moreover, in an era where the federal government treats school-board critics as something akin to domestic terrorists, it takes little imagination to envision how the state might employ a “gang member” firearm prohibition against its political adversaries.

Over the last half-century, gun-rights supporters’ enthusiasm to protect the ownership and availability of the types firearms necessary to exercise the Second Amendment right has altered the political landscape. Now, as gun-control supporters increasingly set their sights on gun owners, gun-rights supporters must marshal that same passion to combat the more complex anti-gun campaign to expand prohibited-persons categories. At stake is more than just what types of guns Americans may own, but whether the average American will qualify to own any firearm at all.