“Wow, if that gun could only talk, I wonder what stories it would tell.”

That’s a quote I’ve heard often while roaming the galleries of the NRA’s National Firearms Museum. As a museum curator for the past 32 years, I can tell you that if you closely examine any firearm, the stories lying hidden within the finely figured wood and highly polished blued steel are worth coaxing out. These are stories that tell of the role guns played in creating history, whether that history be of world, national or just familial importance.

At each of the milestone events of our history, a firearm was likely present. In securing liberty or defending it, firearms have been the tools of the trade that have made freedom possible. From Lexington Green in 1775 to September 11 in New York City, the firearms described here all have remarkable stories to tell. Freedom is found in their metal.

Bringing those stories to light has been an objective of the NRA for decades. Back in 1935, the editors of American Rifleman magazine placed some of the dozens of firearms that they had in their research and evaluation collection on display at the NRA HQ building at Farragut Square in Washington, D.C. The Barr Building, directly across the street from the venerable Army & Navy Club, became the site of the first NRA Museum. In 1998, a new and improved NRA Museum opened at the then-new NRA headquarters building in Fairfax, Va.

Eighty-six years after it first opened, the NRA’s National Firearms Museum now houses over 10,000 firearms and has spawned two satellite museums, one in Raton, N.M., and one in Springfield, Mo., that see a combined total of over 350,000 visitors a year. In reopening the National Firearms Museum in 1998, the new tag line was “Firearms, Freedom and the American Experience.”

What follows here are stories, some well-known and others not so much, but each story is about a firearm and the impact it had in the life of its owner and the history of freedom.

A Shot Heard Round the World

It was late in the evening on April 18, 1775, when Joseph Barnes and some of his fellow members of the local militia gathered at Buckman Tavern on the Green at Lexington, Mass. Alerted by Paul Revere’s “midnight ride” informing the local citizenry of the approach of some 300 British regulars, Barnes and approximately 70 of the members of the militia fell under the command of Captain John Parker, who formed them into ranks on the Green shortly before dawn.

The sudden appearance of British regulars was not uncommon since they had garrisoned in nearby Boston some seven years prior. But Paul Revere had intelligence that this march through the local countryside wasn’t just another regular training exercise. This time, the regulars had specific written orders from their commanding general, Thomas Gage. He wrote: “… you will march with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy all the Artillery, Ammunition, provisions, tents, small arms, and all military stores whatever.” Unlike the training exercises of the past, this time the British were after guns owned by the citizenry.

As Maj. Pitcairn’s Redcoats formed on one side of the Green, Parker told his men: “Stand your ground; don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.”

Within the next few tense seconds, a shot rang out-from where, no one to this day knows-but a full fusillade soon erupted from the British ranks, eight militia members died and 10 more were seriously wounded.

Pvt. Joseph Barnes was armed with an American cherry-stocked, 20-gauge fowler and a carved powder horn. It is unknown if he was able to get a shot off at the British before he and the rest of his company fell back on Concord that morning, but he survived the opening round of the War for Independence and took his fowler with him to Bunker Hill and numerous other battles over the course of the next few years. He served in the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, in Capt. William Walker’s Company. His regiment also saw action at the battles of Saratoga, the Battle of Newtown, the Siege of Boston and Valley Forge. His fowler stayed in his family for generations and was eventually converted from flintlock to percussion so that it could continue to provide sustenance for him and his descendants. A true national treasure, it was witness to the opening fight for American independence. Graciously loaned by Tom Grinslade, ASAC.

From Sea to Shining Sea

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson directed Capt. Meriwether Lewis to assemble a Corps of Discovery from three dozen U.S. Army regulars and explore the recently acquired territory of the Louisiana Purchase. Setting off from Pittsburgh, Penn., Lewis, his co-leader William Clark and their intrepid band of soldiers blazed a path across the vastness of 2,600 miles of uncharted territory. They returned to St. Louis three years later, having amazingly suffered the loss of only one participant.

In 1996, Stephen Ambrose wrote a national bestseller on the expedition called Undaunted Courage. In this remarkable book, Ambrose remarks not once or twice, but three times, on how the expedition had stayed alive. He asked what kept the Indians from just overwhelming them and taking all of their supplies? Surely, given their numbers, they could have easily been overrun. Their firearms and ammunition would have created a new power dynamic for whomever succeeded in capturing them.

What Ambrose didn’t know in 1996, because it wasn’t well known until 2003, was that Lewis and Clark carried a secret weapon with them, a force multiplier, so to speak. Their secret weapon was a Girardoni air rifle, made in Austria in the mid-1790s and originally manufactured to help the Austrians fight Napoleon Bonaparte. This air rifle had a tubular magazine that held 22 .46-caliber round-ball bullets. It fired with such force and accuracy that each bullet could penetrate an inch into wood at 100 yards. You could reload it and fire another 22 shots before the air reservoir needed to be recharged.

The way in which Lewis and Clark used the rifle is the secret to their success. Every time they met a new tribe of Native Americans, Lewis would put on a formal show of introduction to all assembled. He introduced himself and his party, welcomed the tribe into the protection of the United States, gave them peace medals and trinkets as tokens of friendship and then demonstrated the firepower of the air rifle. To say the witnesses were amazed is an understatement. They were terrified of the destructive firepower that only one man possessed. Attempts to gain access to their supplies were politely rebuffed as Lewis wanted to keep them wondering if there were more than one of these guns available to the members of the Corps of Discovery.

So it was a parlor trick, the appearance of peace through superior firepower, that kept unwanted hostilities at bay for over three years. It was a surplus novelty gun left over from the early Napoleonic Wars that assisted in the establishment of the stars and stripes flying from sea to shining sea. Truly, this was a gun of “Manifest Destiny.” Through the generosity of museum patron Michael Carrick of Oregon, both the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Va., and the National Sporting Arms Museum in Springfield, Mo., have an original Girardoni air rifle on exhibit.

Leaves of Grass

Walter “Walt” Whitman (1819-1892) is perhaps the best-known American poet of the 19th century. His first collection of poems, published in 1855 as Leaves of Grass, remains one of the finest examples of literary verse ever produced in this country.

During the Civil War, he worked in the soldiers’ hospitals near Washington, D.C., as a nurse, and at the Army Paymasters Office as a clerk. His volume of verses began to find positive critical reviews, and he became increasingly popular as the war progressed. Some readers, though, found his tome morally objectionable as Whitman, unashamedly, did not go to any great lengths to hide or conceal his emotional attachment to both women and men.

He was once savagely attacked in Washington, D.C., and suffered greatly at the hands of street thugs who bloodied and bruised him, robbing him as well. More than one modern historian has speculated that the attack was instigated by a soldier who was a recipient of an unwanted advance from Whitman. No matter the reason, Walt Whitman, in 1870, purchased a .30-caliber, C. Sharps & Co. of Philadelphia, four-barrel “pepperbox” pistol and had his name engraved on the backstrap. His Sharps was designed by Christian Sharps, who had designed and manufactured the breechloading rifle and carbine that bears his name, both of which saw extensive use from the John Brown raid in 1859 throughout the Civil War. This pepperbox pocket gun was a constant companion of Whitman, the pistol-packing poet, until his death in 1892. Graciously loaned by Dr. Richard Labowskie, ASAC.

For the Increase and Diffusion of Knowledge Amongst Men

In 1829, an English scientist, James Smithson, left a provision in his will to establish an institution in the United States for “the increase and diffusion of knowledge amongst men.” That institution was formed in 1846 as the Smithsonian and remains today as the foremost center of history and science in the country. Few folks, however, know of how a mild-mannered museum curator at the Smithsonian helped produce one of the more-interesting sidearms ever used in military history.

Jean Alexandre Francois LeMat was a native of Paris, France, and had emigrated to New Orleans prior to America’s Civil War. In New Orleans, he met and married a cousin of then-U.S. Army Maj. Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (a relative of this author). LeMat had an idea for a revolver that could also double as a handheld shotgun if needed. In an age when most revolvers allowed five or six shots, the revolver that LeMat and Beauregard designed was capable of firing nine .42-caliber bullets and one 20-gauge shotgun blast from a second barrel that doubled as a cylinder pin.

LeMat and Beauregard had prototypes made by John Krider in Philadelphia, but did not find a market for the gun until the Civil War broke out in 1861. Unable to find a factory in the South capable of manufacturing the gun, they enlisted Charles Girard, a curator at the Smithsonian Institution, to take the gun to Europe to have it manufactured overseas. Girard was able to get the gun produced at factories in England, Belgium and France. Over 3,000 of these fascinating “grape-shot” revolvers were made and run through the Union Blockade during the war. Favored by Confederate Gen. J. E. B. Stuart, his LeMat and holster are on display in Richmond, Va., and no less than five others are on exhibit at the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax.

The Longest Day

History is a collection of events often sorted in the timeline of humanity by the dates on which the events occurred. July 4, Dec. 7 and Sept. 11 are all indelibly marked upon the memories of most Americans. But one day, June 6, 1944, has an additional moniker: D-Day.

For 4,400 of those Allied soldiers who participated in the largest invasion in military history and began the liberation of Western Europe, D-Day became their last day on earth. For the 156,000 who participated and survived, it became the first day of the end of World War II.

American soldiers began, as Gen. Eisenhower put it, their “Crusade” in Europe, on the Utah and Omaha Beaches along the Normandy coast in northern France. Each beach was divided on the campaign maps by sectors that allowed supply and support units to know exactly where they were or needed to be. Easy Red Sector on Omaha beach was one such area, and it saw some of the fiercest fighting as elements of the 1st Division, 16th Infantry, struggled to gain a toehold on French soil. (The actor Charles Durning (1923-2012) earned a Silver Star and three Purple Hearts at Easy Red Sector that morning.)

At one point in the day, a Coast Guardsman aboard the USS Samuel Chase, an amphibious transport ship, recovered a .30-caliber M1 carbine made by the Inland Division of General Motors on Easy Red Sector and took it back with him. Made in 1943, this carbine was manufactured in Detroit, Mich. It was one of 2.6 million M1 carbines made at the former automotive factory and one of 6.1 million made overall. It was the most-mass-produced firearm in American military history at the time. John Ewing, of the American Society of Arms Collectors, has generously loaned it to the museum for special exhibits.

Go Ahead and Make My Day

It would be hard to identify a firearm that has more recognition than the .44 Magnum Smith & Wesson Model 29 used by Clint Eastwood in the series of Dirty Harry films he made beginning in 1971. It is perhaps the most well-known firearm in the world.

Former NRA Board Member John Milius gifted the revolver currently on display in our Hollywood Guns exhibit. Clint Eastwood gave the gun to Milius in gratitude for his contribution to the first two Dirty Harry films as a script writer.

To hear Milius tell the story, it was Frank Sinatra whom director/producer Don Siegel first approached to be the offbeat San Francisco detective known as “Dirty Harry.” Sinatra was excited to be a part of the project and even proudly fetched his own Colt Detective Special to show that he had more than a passing familiarity with handling firearms. He was not, however, very excited to learn that the script called for the gun, not so much the actor, to be the main focus of the storyline. He politely passed on the project as the Smith & Wesson was too large and heavy for him to handle, since he had just had surgery on his hand following an on-set accident received in a fight scene with fellow actor Lawrence Harvey in “The Manchurian Candidate” (1962). Needless to say, what was Sinatra’s loss was Eastwood’s gain.

Milius’ first inclination had been to equip Detective Callahan with an 8-inch magnum, but trying to find a trio of them was somewhat problematic. None of the studio prop houses had three 8-inch Model 29s. A search of California gun shops turned up the needed three guns at a police supply store in Los Angeles, but only with 6-inch barrels. The studio settled for the 6-inch versions, and the rest, as they say, is film history. Milius’ screen-used revolver has been one of the most-popular exhibit highlights of the museum since its donation in 2002.

September 11, 2001

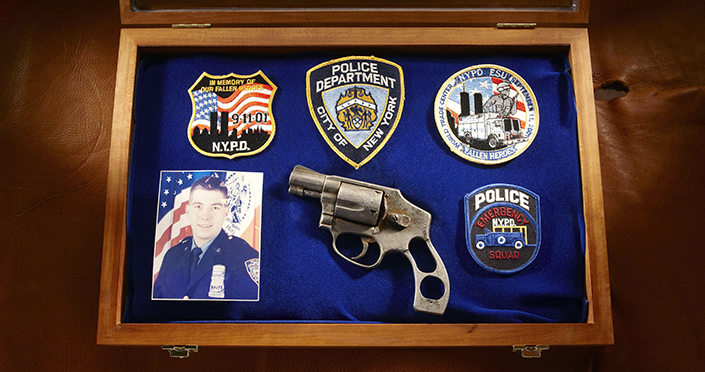

New York police officer Walter Edward Weaver, shield #2784, was known as “Wally” to his family, friends and colleagues. A nine-year veteran of the New York Police Department, he had exerted a great deal of time and effort to qualify for the Emergency Services Unit of the NYPD and, once accepted, moved from Precinct 47 to Squad 3 of the ESU stationed in the Bronx. Sept. 11, 2001, was to have been one of his well-earned days off, but he offered to substitute for a friend and pulled a shift in lower Manhattan that morning. He was last seen on the sixth floor of the North Tower shortly before it fell. He was one of 72 law-enforcement officers who perished that day. Officer Weaver was a proud NRA member, and his parents felt that his Smith & Wesson Model 640-2, recovered from the North Tower debris, would be best displayed at the NRA Museum so that all who saw it would be reminded of the sacrifices so many made that September morning.

These seven firearms represent 226 years of American history. Whether found in the first shots in the war for Independence or the opening scenes in the ongoing Global War on Terrorism, whether protecting a cultural treasure or representing Americans’ independent culture on the screen, firearms of many types, styles and calibers are a key part of our history. They differ, yet they have one feature common to all: There is freedom in the metal.