This feature appears in the February ‘16 issue of NRA America’s 1st Freedom, one of the official journals of the National Rifle Association.

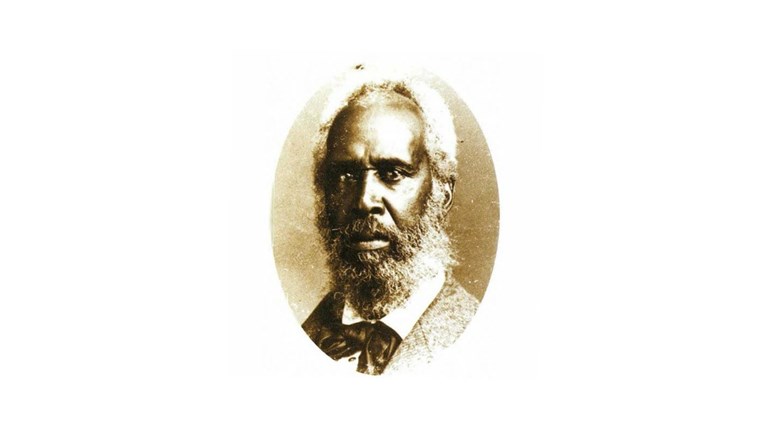

He was the most photographed American of the 19th century, an eloquent advocate of the right to arms. She exercised that right heroically, in armed missions to lead slaves out of bondage. Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman exemplified the best of America—and fought against the worst.

When Congress passed the 14th Amendment in 1866, why was its protection of Second Amendment rights considered so important? In the Supreme Court’s decision in McDonald v. Chicago, Justice Clarence Thomas turned to Douglass for that answer.

As quoted in Justice Thomas’ concurring opinion, Douglass delivered a major speech in New York City on May 10, 1865, one month after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, Va. Everyone knew that formal slavery would soon be abolished. But would the ex-Confederate states find new ways to keep the ex-slaves in de facto servitude? That was the question posed by Douglass’ speech “In What New Skin Will the Old Snake Come Forth?”

Presciently, Douglass warned that the ex-slave states would attempt to impose all sorts of disabilities on the freedmen, as they had on free people of color before the Civil War. Douglass explained that abolishing slavery was not enough. There was a need for federal law to stop state and local governments from infringing the freedmen’s rights, especially the right to bear arms. The Klan was America’s first domestic terrorist organization, and first gun control organization.

Without such legislation, he said, “The legislatures of the South can take from him the right to keep and bear arms, as they can—they would not allow a negro to walk with a cane where I came from, they would not allow five of them to assemble together.”

“Notwithstanding the provision in the Constitution of the United States, that the right to keep and bear arms shall not be abridged, the black man has never had the right either to keep or bear arms.” Until there was a new constitutional amendment to make states obey the Second Amendment, “the work of the abolitionists is not finished,” Douglass said.

As he pointed out, blacks in the slave states had effectively been denied the right of personal self-defense. Because blacks could not testify in court against a white, a white could commit violent crime against a black with impunity, as long as there were no white witnesses. Further, the slave state codes made it a crime for a black man to “lift his arm in self-defence” against a white.

Douglass was born a slave in Talbot County, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1818. When he was about 12 years old, his owner’s kindly wife began teaching him to read. The owner ordered her to stop, because literacy would “make him forever unfit to be a slave.” But Douglass’ thirst of knowledge was unquenchable, and he surreptitiously taught himself to read well—and reading did make slavery intolerable to him.

He illegally taught dozens of other slaves to read. Douglass was sent to work for Edward Covey, who was known as a “slave-breaker.” After half a year of beatings, the 16-year-old Douglass fought a two-hour brawl with Covey that ended in a draw. There were no more beatings.

For Douglass, “This battle with Mr. Covey was the turning point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood.”

Douglass’ third attempt to escape succeeded in 1838. Assisted by the Underground Railroad, Douglass made his way to New York City. When he arrived, he felt a “joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe.”

Soon, he was working with the abolitionists and giving lectures about the true experience of slavery. As he educated himself, his many speeches were laced with allusions to classical Rome, Shakespeare, European history and American poetry.

His autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, was published in 1845, and to this day remains central in the American literary canon. On a speaking tour in England and Ireland, he became friends with the Irish leader Daniel O’Connell, who was trying to help his people shake off the yoke of centuries of English rule. Like the blacks of the slave states, the Irish Catholics were disarmed lest they rebel against government without their consent.

Although some abolitionists thought that the U.S. Constitution was pro-slavery, Douglass, after reading Lysander Spooner’s 1846 book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, disagreed. Among Spooner’s arguments was the Second Amendment: Its provisions “obviously recognize the natural right of all men ‘to keep and bear arms’ for their personal defence. … The right of a man ‘to keep and bear arms,’ is a right palpably inconsistent with the idea of his being a slave.” Yet slave states prohibited arms possession by slaves. Ergo, slavery is unconstitutional. Of course, “This constitutional right to keep arms implies the constitutional right to use them, if need be, for the defence of one’s liberty or life.”

At the beginning of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln was reluctant to allow the Union Army to liberate slaves, or to permit blacks to serve in Union ranks. Congressional pressure for armed blacks was led by Illinois Sen. Lyman Trumbull. After the Civil War, Trumbull would become the sponsor of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Act, the first federal laws to protect the Second Amendment right to arms.

As the war dragged on and casualties mounted, military necessity and congressional action forced Lincoln to accept Trumbull’s proposals for armed black soldiers. During and after the war, the thought of armed blacks was terrifying to racists. Justice Thomas quoted the words of anti-slavery Rep. Thaddeus Stevens: “When it was first proposed to free the slaves, and arm the blacks, did not half the nation tremble? The prim conservatives, the snobs, and the male waiting-maids in Congress were in hysterics.”

To Douglass, the 200,000 black men who served in the Union Army proved that blacks had a right to vote, for they now carried “a Springfield rifle” in combat. (Jan. 13, 1864). Agitating for a constitutional amendment for voting rights, Douglass reminded the American public, “The black man came to you in your hour of danger, of trial, when your flag wavered, reached out his black iron arm, and clutched your standard with his steel fingers.” (May 12, 1869). Douglass’ goal was achieved in 1870 with the ratification of the 15th Amendment. As she later explained, “I can say what most conductors can’t say—I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

Douglass continued his career as a touring speaker, in America and abroad, for most of the 19th century. Among his causes were home rule for Ireland, women’s right to vote, and federal protection of the civil rights of all people, regardless of color. As he put it, “Keep no man from the ballot box or jury box or the cartridge box, because of his color.” (Feb. 7, 1867).

Douglass also served in the Republican administrations of presidents Ulysses Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes and James Garfield—including as a diplomat to the Dominican Republic, and as U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia. Douglass recalled that he “was never received by any gentlemen in the United States with more kindness, more cordiality” than in Grant’s home. (July 25, 1872).

After retiring from the presidency in 1877, Grant would soon be elected president of the National Rifle Association. Although eight U.S. presidents have been NRA members, Grant is the only man to have been president of both the nation and the NRA. Douglass also had high praise for another future NRA president, “gallant Phil Sheridan,” for carrying out President Grant’s program to eradicate the Ku Klux Klan. (Sept. 26, 1875). The Klan was America’s first domestic terrorist organization, and first gun control organization.

Late in life, Douglass began working with Ida B. Wells—a young journalist and former slave who was one of the leading voices for the rights of people of color and of women. As lynchings increased, Wells urged that “a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give. … The more the Afro American yields and cringes and begs, the more he has to do so, the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched.”

Railroad To Freedom

Harriet Tubman was born around 1822, a slave in Dorchester County, on the southern tip of Eastern Shore Maryland just south of Douglass’ Talbot County.

Her family’s owner made plans to sell her younger brother, Moses, to a man from Georgia. Like his namesake, Moses was hidden for a while by other slaves and by free blacks. Eventually the ruse was discovered, and the owner approached the family home to seize Moses. Tubman’s mother confronted them: “You are after my son; but the first man that comes into my house, I will split his head open.” The sale was abandoned. The example of forceful resistance inspired Tubman’s later actions.

When her owner died in 1849, there was an imminent risk that her family would be broken up as part of an estate sale. Tubman resolved to escape. As she later recalled, “There was one of two things I had a right to: liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.”

In October 1849, she escaped, leaving a coded message for her mother: “I’ll meet you in the morning. I’m bound for the promised land.”

The Underground Railroad delivered her to the free state of Pennsylvania. “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person,” she wrote. “There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

She settled in Philadelphia and immediately set to work to rescue her family and others. As a conductor on the Underground Railroad, she ran 13 missions over the next 11 years, rescuing at least 70 slaves, perhaps many more. For obvious reasons, she kept no records.

Tubman carried an old percussion pistol for protection against slave-catchers and their hound dogs. This violated an 1806 Maryland statute, which forbade “any negro or mulatto within this state to keep any dog, bitch or gun.”

The pistol was also a threat against any faint-hearted fugitive who wished to turn back. As Tubman knew, any slave who returned would be tortured into revealing everything about the remaining fugitives, which would result in the whole group being captured. Pointing her gun at one escapee, who was exhausted and hungry after a day of hiding in a swamp, she told him, “Move or die.” She delivered him and the others to freedom soon after.

As she later explained, “I can say what most conductors can’t say—I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.” Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison nicknamed her “Moses,” as she too led people from bondage to freedom.

In 1850, Congress enacted a very severe Fugitive Slave Act.

But it was also Northern whites who felt the injustice of the new act. Like state and local governments, the federal government has an inherent posse comitatus power. A federal marshal or a county sheriff may summon armed men to assist him in enforcing the law. In modern Colorado, for example, sheriffs have used their posse authority to deter looting after the catastrophic floods in September 2013, and to assist with manhunts for escaped criminals.

Although antebellum northern Americans were generally happy to perform their posse duties, they were revolted at the Fugitive Slave Act’s compelling them to assist federal slave catchers. The posse comitatus was supposed to be the people of the county participating in self-government by enforcing their own laws. Now, federal posse comitatus had been perverted into a weapon that transformed free citizens into the minions of distant slave owners.

According to the abolitionists, there were now only two choices for a free northern man: To himself become a servant of the slave power in the federal posse comitatus; or to put slavery on the road to extinction. The Fugitive Slave Act nationalized the issue of slavery, infuriated much of the North and was a major contributor to the outbreak of the Civil War.

Because of the Fugitive Slave Act, Tubman began taking her passengers all the way to Ontario, Canada, beyond the reach of federal power. On one occasion, she led 11 fugitives to a temporary resting spot at the home of Frederick Douglass in upstate New York.

During the Civil War, Tubman volunteered to help the Union army. Initially, she was a cook and nurse. But her talents were later put to better use as a scout and spy based near Port Royal, S.C. The marshy terrain there was similar to the familiar Eastern Shore of Maryland, and she was expert at moving covertly. She commanded a group of eight other scouts, and reported directly to Gen. Rufus Saxton. (In 1866, Saxton complained to Congress that armed bands were seizing blacks’ firearms in South Carolina, violating their Second Amendment-protected rights. The U.S. Supreme Court in the 2008 Heller case quoted Saxton’s words.)To Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, the right to arms was part of the difference between slavery and freedom.

On June 1-3, 1863, Tubman guided the Union raid at Combahee Ferry, S.C. Three small U.S. Navy gunboats traveled up the coastal Combahee River, carrying black soldiers and their officers. Tubman was the first woman to lead an armed force during the war. Instead of a handgun, she now carried a percussion rifle—probably a .50-caliber model similar to the Hawken Rifles favored by mountain men before the war.

The raid was a complete success. The Union forces destroyed a bridge, seized vast amounts of supplies from the immense plantations in the area and liberated 600 to 750 slaves. Tubman led about a hundred of the freedmen to the recruiting station at Hilton Head, where they promptly enlisted in the Union army.

The Combahee Ferry raid into the “Cradle of Secession” was used as a model for future raids, such as the one at Darien, Ga., which is portrayed in the movie “Glory.” The excellent performance of the black soldiers at Combahee strengthened the hand of the recently appointed commander of the Army of the Potomac, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who was a leading advocate for allowing blacks to fight for their freedom. (In 1871, Burnside would become the founding president of the National Rifle Association.)

With a heavy price on her head, Tubman repeatedly risked her freedom—and her life—in order to liberate others. As Douglass wrote to her in 1868: “‘God bless you’ has been your only reward. The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism.”

After the Civil War, Tubman became an activist for women’s suffrage. Her speeches explained the sacrifices that women, including herself, had made for liberty. At the founding meeting of the National Federation of Afro-American Women in 1896, Tubman delivered the keynote speech. She created the Harriet Tubman Home to care for aged and indigent blacks. Outside of New York City, it was the only charity in New York state that attended to black people.

Intensely religious, Tubman’s greatest inspiration came from the Old Testament stories of the liberation of slaves, such as the Hebrew Exodus from Egypt. She is honored in calendars of saints of the Episcopal Church and of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. One of her formal recognitions as an American hero is the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland.

Both Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass opposed movements to send ex-slaves to Africa. “We’re rooted here, and they can’t pull us up,” said Tubman. Both of them greatly admired the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and both dedicated their lives to making them apply equally to all Americans.

To Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, the right to arms was part of the difference between slavery and freedom—in the very immediate sense of the Underground Railroad, and in the broad sense embodied in the 14th Amendment. Born a non-citizen slave, made a citizen by the 14th Amendment, Douglass called American “citizenship beyond all others on the globe.” (Sept. 25, 1872).

Douglass’ speech memorializing the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison applies just as well today as we remember the contributions of Tubman and Douglass: “Let us guard their memories as a precious inheritance, let us teach our children the story of their lives, let us try to imitate their virtues, and endeavor as they did to leave the world, freer, nobler, and better than when we found it.

Editor’s Note: Further reading—Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman (Back Bay Books, 2004); William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass (W.W. Norton, 1991); The Frederick Douglass Papers, series one, Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, volume 4, 1864-80 (Yale Univ. Pr., 1991); Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (First published in 1845). Note that all Douglass quotes without date cites are from Narrative.