Ask almost anyone who is good at something how they got that way, and the answer is quite frequently dull. Stripped of the interesting, even awe-inspiring externals, the internals are binary and mundane: Winnow out the inessentials, and practice, practice, practice.

Shooting follows this pattern particularly well. Sight picture and trigger press are critical across the board, and extremely transferrable. The rest, by comparison, are nuances. It doesn’t mean those nuances or special cases aren’t important; rather, that they cannot reliably substitute for core capacities no matter how liberally, expertly or rapidly they’re applied.

When it comes to defensive shooting, however, other nuances can become so complex and variable that our mechanical skills may emerge as an actual problem in their turn: Just because we can shoot (even with superb speed and precision) doesn’t mean we should.

Think this through, and you’ll shortly see a common thread in our practice modes that reinforce this. The vast preponderance of drills end with one or more shots. It’s to be hoped that real-world situations only rarely correspond, but how do you prep for such an unwelcome chance? Just because we can shoot, even with superb speed and precision, doesn’t mean we should.

Not long ago, we talked about danger targets. We posited two difficulties in addressing these: They’re “shapes” that don’t work as well with the brain’s concentricity bias (a natural aim point is harder to come by and therefore slows us down), and penalties for poor shots on such targets—both in competition and the real world—compound rapidly. A good way to think about shoot/don’t shoot practice is as predecessor and successor of both.

The successor part is—comparatively—easy. You should practice shooting asymmetric, irregular targets simply because they are far more likely to proxy what you would face in a defensive situation. The fact that such targets are more difficult and the situations they mimic are deeply unwelcome are not good excuses for failing to train for them.

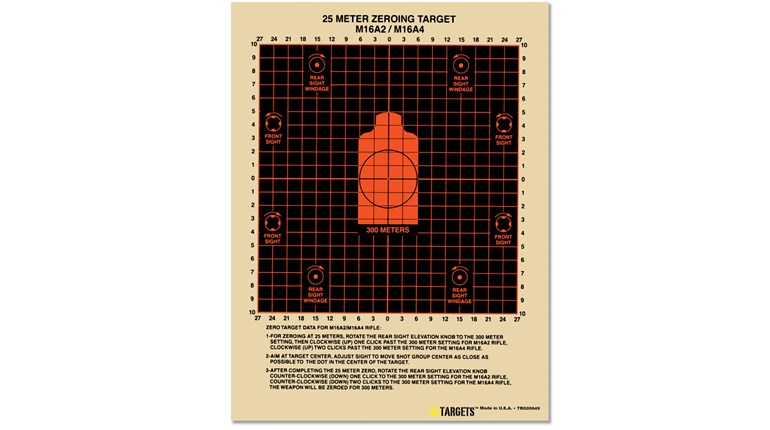

Photorealistic targets are one way to practice these shots, and not a bad one. The trick is to get enough variety, and unless you’re willing to shell out a small fortune, these become rote like any other target can. Their visual “flatness” tends to add an unfortunate element of unreality, but within the limits of printing technologies that keep them remotely affordable, this is hard to fix. They’re worth using all the same, but mix ’em up. (A favorite here.)

The predecessor notion is where practice gets both crucial and difficult. Mainly, this is due to the fact that if you set your target, you know what and where it is with precision, and you can’t simply “forget.” In your head at least, you have a jump on solving the problem that leaves out a vital observation and decision process that needs to happen in the real world.

We suggest there is a (surprisingly) sound drill that helps, and has the advantage of requiring no special equipment—just a vision barrier or two, some tape, colored paper (card stock is ideal; easy to cut, but more wind and reuse-resistant), a pair of scissors—and the company of a shooting pal. If it initially strikes you as a little kindergartenish, well, bear with us. Or get your kids to help.

Either way, cut out some shapes that correspond to everyday objects—a purse, wallet/billfold, cellphone, baby bottle, tablet computer or laptop, coffee cup, ruler, water bottle, etc. It’s desirable not to make these overly perfect, nor all in plan view; give them aspects or views that don’t make them too easy to identify.

Next, cut out some clear weapons—and not just firearms or knives. A crow bar, hammer, even a facsimile of the scissors you’re using are good candidates. For both sets of these props, use realistic and unrealistic colors.

If just this prep gives you a bit of an “Aha!” moment, then we’ve already accomplished much of our purpose: This predecessor notion that most of our shooting practice leaves out is a threat assessment combined with the presence of a credible weapon, versus the presence of everyday objects in ambiguous situations.

We can hear you giggling. “Really,” you’re saying, “a paper cellphone cutout tapped over the gun on that man-grabbing-the-woman-around-the-neck target fixes what bad shooting habit, exactly?!”

None, perhaps; but we warned you this wasn’t a shooting exercise, per se. You’ll get the idea in a hurry about how complex circumstances can become.

What it should demonstrate to you is that uninspected (“surprise”) courses of fire can combine with postures and everyday objects to deeply muddy our perceptions of actions, expressions and—most of all—intentions, harmful or otherwise. This effect is magnified by the unfamiliar in terms of people and places. The photorealistic horror on the woman’s face may only be surprise, and the man behind her a beloved, extending not a pistol at you, but his cellphone to show her the latest hilarious Facebook post of who-knows-what. Did that end-with-a-shot reflex make you draw, rounding the vision barrier, when you saw his arm around her? Did you shoot?

For most, it only stays trivial until you shoot a good guy target. It’s amazing the time it can take to be sure a crowbar isn’t a cane, or more ambiguous yet, tell a “good” hammer from a “bad” one.

We grant that such simulations have obvious limits. But don’t, as the old saying goes, “knock it until you’ve tried it.” If your shooting partner (or partners; more are better for this) mixes shoot and don’t-shoot presentations well enough, you’ll get the idea in a hurry about how complex circumstances can become, but also that the responsibility for getting it right rests wholly on you.

You can put more pressure into this exercise by adding a “par time” to limit the transit interval between a start and finish position, or use an encumbrance—a largish package or simulated child. Lane-only practice or always-shoot weaknesses really tend to leap out under these circumstances. That said, watch for safety issues: This exercise adds complexity in a hurry, so build your skills over time. Recognize that adjustment for the less-experienced shooters is a likely requirement.

A simplified version of this can work indoors, too. If your range has target carriers that turn in both directions (most do, these days), one side—and unknown to the shooter which side—is a “shoot scenario,” the other a “no-shoot.” Add a “charge” toward the shooter, and this is an even better drill. This can be usefully jarring, though it doesn’t embody the outdoor advantages of vision barriers, more decision points, and assessment/engagement while moving. In either venue, don’t overlook an obvious curve to throw your training partner(s) by making all options “shoot” or “no-shoot.” We add non-target “shoot-me” signs to all “no-shoot” scenarios so the lack of shots doesn’t tip off shooters who have yet to work the stage.

Our point here is simple: Regular practice lacks the components to prepare us for this kind of discrimination, and simply thinking about it is a weak solution. It also begs a big picture sort of question, and one we can’t responsibly ignore: always be sure beyond a reasonable doubt that a shot is necessary. Good situational awareness and genuine civility can go a long way to keeping us out of that sort of trouble, but practice what you can to get and keep what may prove to be a vitally sharper edge.

Editor’s Note: Prefabricated targets for threat discrimination are an excellent shortcut in many respects, but don’t offer the variety you can create yourself. Some are available here.