Imagine if California, to combat what the Legislature considered the serious problem of manmade global warming, required all new vehicles sold by car dealers in the state to run on grass clippings, rather than fossil fuels.

Would it be fair to say that California was legitimately addressing serious environmental problems and promoting innovation? Or would the more obvious conclusion be that California simply wanted to ban the sale of new cars?

If you agree with second option, you’d likely be in the minority of a recent 9th Circuit Court of Appeals panel that found another non-existent technology—in that case, Pena v. Lindley, a microstamping requirement that applies to newly introduced semi-automatic pistols—to be consistent with the Second Amendment.

In other words, two out of three judges ruled design requirements that no manufacturer can satisfy—nor that are useful enough to be in development by any manufacturer—can still be a prerequisite for the lawful commercial sale of constitutionally protected handguns in the state.

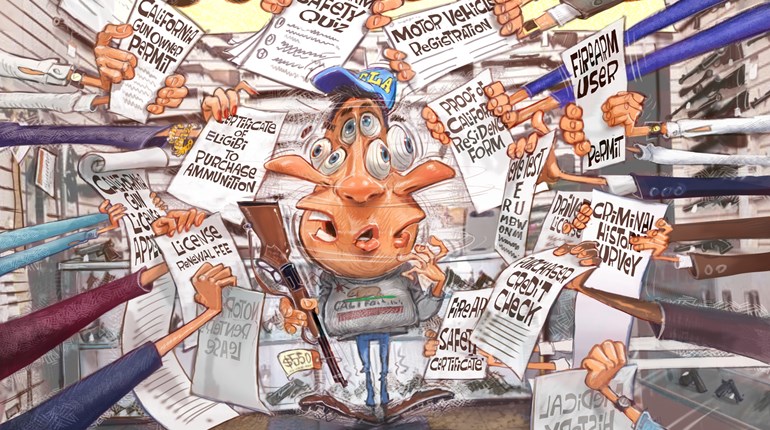

The dispute stems from California’s so-called “Unsafe Handgun Act” (UHA).The UHA purports to promote public safety by weeding out “unsafe” handguns from commercial sale by a series of design requirements for semi-automatic pistols that must be met by handgun manufacturers. These include a “chamber load indicator,” a “magazine detachment mechanism” (to prevent firing of the pistol with the magazine removed) and a requirement that the pistol legibly imprint an array of information (including the firearm’s make, model and serial number) on two locations on each fired cartridge case. The microstamping requirement took effect in 2013, when state officials determined “that the technology used to create the imprint is available to more than one manufacturer unencumbered by any patent restrictions.”

Significantly, the state’s dual microstamping standards were not designed around proven, existing technology. Rather, they were purposely designed to force manufacturers to develop and adopt technology that was not yet available in the commercial sphere. To date, however, no manufacturer has done so.

The upshot is that the only firearms that may be commercially sold in the state are designs that existed before the date in 2013 on which the microstamping mandate took effect. Such models are “grandfathered” under the law. Any changes to the design—including non-mandatory safety features that weren’t incorporated in 2013—requires the model to be retested and to meet the current standards, including those pertaining to microstamping.

The irony is that California’s law effectively deprives state residents of market-driven changes in design available to residents of other states that improve the safety and utility of modern pistols. Indeed, the law virtually ensures that there will come a time when the only semi-automatic pistols lawfully available for sale in California will be used models that are many years old.

None of that, however, bothered the two judges in the panel’s majority, who breezily concluded that even if the law burdened conduct protected by the Second Amendment, the state’s “public safety” interest and legislative “fact-finding” satisfied the low bar of “intermediate scrutiny.”

Yet even by the standards of politically motivated judicial activism, the majority did not—as the dissent indicated—“take Plaintiffs’ Second Amendment claims seriously.” Indeed, the majority opinion—written by Judge Mary Margaret McKeown—is riddled with errors that have nothing to do with legal opinion or judicial philosophy, but that simply misstate or misrepresent plain facts.

Perhaps most embarrassingly, McKeown seemed unaware of the difference between bullets and cartridge cases when analyzing the strength of the state’s interest in enforcing its microstamping requirement. McKeown cited a prior case from another circuit that held that the ability to conduct serial number tracing on firearms constituted an important state interest. “The same logic applies to recovered bullets, and counsels the conclusion that limiting the availability of untraceable bullets serves a substantial government interest,” she wrote.

Yet the law does not require fired bullets to be microstamped. Rather, it requires fired cartridge cases to be microstamped. While a criminal investigator might be able to tell which firearm ejected a particular cartridge case, that would not necessarily determine whether a bullet, even of the same caliber recovered at the same scene, came from the same gun. Indeed, cunning criminals could switch firing pins between guns of the same make and model or drop previously fired cartridge cases at a crime scene specifically to confuse criminal investigators.

Thus, McKeown apparently didn’t understand to which component of a round of ammunition the microstamping requirement applies, or she didn’t understand the difference between a fired bullet and a spent cartridge case. These differences, however, are crucial in understanding why people who are knowledgeable about firearms are so skeptical about microstamping’s usefulness. Microstamping could produce a lead in a case, but it could just as easily be used to plant a red herring.

Regarding the state’s certification in 2013 about the “availability” of the technology, the dissent noted “this certification confirms the lack of any patent restrictions on the imprinting technology, not the availability of the technology itself.”

“If the requirement is impossible to comply with,” the dissent concluded, “it imposes a burden without advancing any state interest.”

Reduced to their essence, the facts of the case strongly suggest that the state’s real goal is simply banning modern pistols, which of course is an outcome that any fair reading of the U.S. Supreme Court’s prior Second Amendment cases would prohibit.

Needless to say, that precedent is not getting a fair reading in most decisions of lower courts, with Pena v. Lindley being just the latest and among the more egregious examples.

President Donald Trump’s nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh for the Supreme Court could mean that help is on the way. In the meantime, however, lower courts are continuing to thumb their noses at the Second Amendment and the Heller majority, even to the extent of sanctioning broad bans on firearms that law-abiding people overwhelmingly choose for self-defense.