The era of the “ace,” that rare blend of superb pilot and—usually—master gunner, is almost certainly drawing to a close. Though the count is tricky to calculate because American aces have served in other allied air forces and not all aces are pilots, the total remains a surprisingly small number. Fewer than 1,500 U.S. aircrew have achieved the lofty status based on five or more air-to-air victories over the more than 100-year history of United States military aviation.

The vast preponderance of aces from all nations achieved their scores in World War II. Even a modest knowledge of aviation history makes plain why: Piston-engined, propeller-driven aircraft of tremendously varied types were fielded by major combatants in positively huge numbers, and in theaters of combat that quite literally spanned the globe. These aerial armadas clawed each other from the skies in “dogfights” that sometimes embroiled hundreds of aircraft.

By the time the Korean conflict flared in 1950, several factors indicated that air-to-air tallies would likely never be the same. The first was purely a numbers effect: More sophisticated, more expensive jet-powered aircraft were not fielded in similar numbers in the much smaller geographic confines of the Korean peninsula. Technology too played a big role. Faster aircraft were operating in more dogfight airspace (in terms of altitude), yet air-to-air weapons were little improved. It was simply tougher to successfully engage considerably faster jet-powered aircraft (50 percent faster, or more in some cases) with machine guns that weren’t greatly superior to those of 10 years before.

July 11, 1953, is in some ways the unlikeliest of our ace tales, as it concerns a Marine pilot flying and fighting in the wrong airplane and the wrong service. Major John Bolt was a very experienced pilot with a lot of jet time in the McDonnell F2H “Banshee,” and had already achieved ace status in World War II with VMF 214 (the famed “Black Sheep,” commanded by none other than quintuple ace [26], Medal of Honor and Navy Cross recipient Col. Greg “Pappy” Boyington).

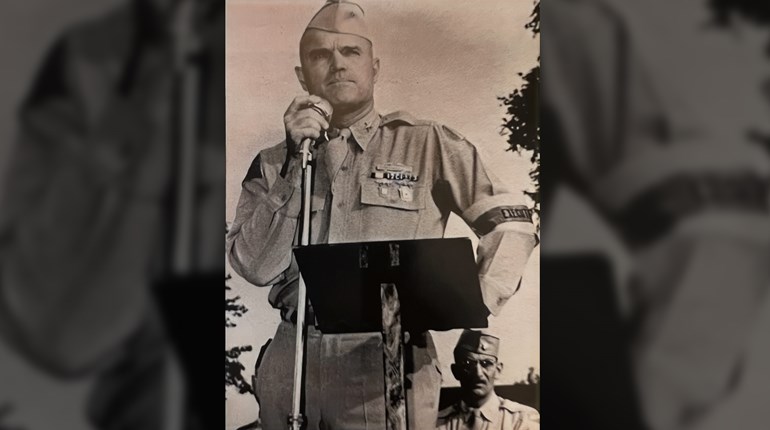

How Bolt engineered an interservice exchange assignment to fly the USAF’s North American F-86 “Sabre,” (the only U.S. airplane that was matching up remotely well against Soviet-supplied and often flown MiG-15) was a trick many of his Marine fellows would have no doubt liked to repeat. Assigned to fly with Lt. Joseph C. McConnell—the eventual top ace for all services in Korea with 16—Bolt made good use of McConnell’s F-86 expertise. In less than two months, he became the Marine Corps’ only Korean ace and last ace, recording all five of his victories against the tough MiG-15. Bolt earned a Navy Cross for his exploits and retired from the Navy in 1961.

USAF Captain James Jabara would fly the F-86 to triple ace status just four days later. Like Major Bolt, Jabara had World War II combat experience and air-to-air victories, though he had not reached ace. He was a relatively early jet pilot, flying the F-80 “Shooting Star” in 1948 before transitioning to the Sabre. Jabara arrived in Korea in December 1950 but did not score his first victory until early April. Three more followed in quick succession, and when his unit rotated back to the United States, he requested a transfer in order to remain in Korea. On May 20, 1951, his gambit paid off in a “MiG Alley” engagement where he became the first jet ace, and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (precursor to the Air Force Cross).

Jabara—now a major—returned to Korea in the spring of 1953, and by mid-July added nine more victories, ending the conflict as the second-highest scoring U.S. ace. He would go on to many prestigious assignments, as well as to pilot many significant aircraft (F-104, B-58). Tragically, Colonel Jabara was killed in a traffic accident with his 16-year-old daughter Carol Anne in November 1966.

Navy Lieutenant Guy Bordelon was similarly busy in those last weeks of the conflict. Flying the Chance Vought F4U of WWII fame in a night-fighter role, he was credited with five victories between June 29 and July 17. In doing so, Bordelon became the only U.S. Navy ace of the war, as well as the only “night” ace, and the only and last piston-engine ace. Bordelon received the Navy Cross, and eventually rose to the rank of Commander in a 27-year career.

Just eight days before the war ended, two more USAF pilots would reach double-ace status (July 19). Lt. Col. Vermont Garrison was already an ace from World War II at the “advanced” age of 28, and spent over a year as a POW in that conflict. When he scored his tenth jet victory at the age of 37 in Korea (Jabara, for instance, was nearly eight years his junior), it’s small wonder he was widely known as the “The Grey Eagle.” (Korea wasn’t Garrison’s last war, either; he added another 97 missions in Vietnam.) Col. Garrison retired in 1973, a Distinguished Service Cross winner (second only to the Medal of Honor), and one of only seven propeller and jet aces.

Captain Lonnie R. Moore also became a double ace on July 19. Another pilot with World War II combat experience (54 missions in medium bombers), he was shot down twice, but evaded capture both times. He remained in the Air Corps after the war, and moved into the separate United States Air Force when it split from the Army in 1947.

His initial trip to Korea was intended to be temporary: He was there to test a new “upgunned” F86-F-2, wherein the six .50-caliber machine guns were replaced with the M39 20mm cannon. In the hands of the expert Moore, the new gun system downed two MiG-15s during the test. Moore stayed in Korea, completing 100 missions and shooting down eight more MiGs. Like Garrison, he won the Distinguished Service Cross for Korean service. Sadly, then-Major Moore would die in a F101 “Voodoo” crash just two and a half years later.

A single thought springs to mind as we look back to this long-ago week in a poorly remembered, misunderstood war. While it comes from the pages of a period novel, we still find truth and gratitude in the words of James Michener’s Admiral George Tarrant (played so memorably by Fredric March in the movie version of “The Bridges at Toko-Ri”): “Where do we get such men?”