When Project Veritas founder James O’Keefe went to buy a shotgun last August 6, an FBI background check barred him from completing the purchase.

O’Keefe came out swinging by quickly posting a video response that stirred up a lot of media attention. As he is the founder of Project Veritas, a nonprofit that uses undercover cameras and informants to uncover waste, fraud and illegal activity, he wondered if he had been blacklisted by the government as a punishment for his many video releases.

O’Keefe also filed a lawsuit against the FBI. According to the complaint, filed in U.S. District Court in the Southern District of New York, O’Keefe alleged that the FBI falsely claimed he’d been convicted of a felony and “has subsequently repeatedly, wrongfully and without justification denied Mr. O’Keefe the ability to purchase a firearm.”

However, the thing about this denial is, it’s much more likely this was simply a bureaucratic hiccup from a cumbersome governmental system.

In 2010, O’Keefe and three of his associates were arrested for entering federal property under false pretenses. The group had dressed as telephone repairmen to gain access to then-Sen. Mary Landrieu’s (D-La.) office in a federal building in New Orleans. When they were nabbed, O’Keefe ended up pleading guilty to a low-level Class B misdemeanor. This misdemeanor doesn’t legally prevent O’Keefe from purchasing or owning a gun, but it’s likely that the initial charge raised a red flag in the system that stopped the sale.

NICS evidently found the correct record and removed the flag on August 14. Someone from the gun store then called O’Keefe to tell him he could buy the gun after all. This delay could have been avoided had a NICS examiner quickly located the correct record on the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) database; but then, to be fair, NICS has been overwhelmed with background-check requests this year.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with having a healthy mistrust of the system, but, as this was being written, it seems clear that O’Keefe was more likely a victim of government ineptitude rather than intentional malfeasance. Whatever the case, this incident does tell us that more people need to understand NICS’ imperfections and its stated purpose.

Fighting Registration

NICS is well known to gun owners as the FBI entity that gun dealers call to clear someone who wants to buy a firearm. Gun sales have soared this year due to the uncertainties caused by the coronavirus, nationwide rioting and a potential Biden presidency. Meanwhile, though NICS has never been a perfect system, 2020 has strained the system to its limits.

You know the routine. When you decide which gun to buy, you fill out the ATF Form 4473 certifying under penalty of perjury that you are not a felon or otherwise disqualified to receive a firearm. The dealer then contacts NICS, which may clear you in a few minutes or may wait no more than three days to research its records, after which you can buy the gun if no disqualifying record pops up. If you are denied based on incorrect records, you may appeal.

NICS is required to destroy all records about the sale, except for an identifying number and the date, within 24 hours of clearing the buyer. This requirement follows a long tradition of the rejection of gun registration in American history. In light of the experiences of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia regarding gun confiscation and tyranny, Congress declared, in the Property Requisition Act of 1941, that Second Amendment rights prohibit the registration of firearms. Legislators, when enacting the Gun Control Act of 1968, also rejected gun registration. Later, the Firearm Owners’ Protection Act of 1986 also prohibited the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (now the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives), or ATF, from creating any system to register gun owners.

In the late 1980s, the Brady anti-gun lobby was promoting a national waiting period for handgun purchases. The early bills included no background check. The NRA advocated that Congress study the feasibility of a background check with no waiting period and with a requirement that the records would be destroyed. Brady then copied the background check idea, but would have allowed the government to keep the records.

In debate, Sen. Orrin Hatch (R) argued that “the Brady bill is a step towards gun registration.” Sen. Ted Stevens (R) said, “We have all heard, my generation did, about Hitler and how, in country after country, he read the gun registration laws and took the guns away from those who had them.” Police and the federal government, he feared, would “compile lists of handgun buyers,” the goal of which was “national registration with the intent of confiscation of guns.” Thus, Stevens offered an amendment that “will not permit the registration of either a gun or a gun owner; in fact, the amendment specifically prohibits keeping any records about lawful sales.”

NICS is only as good as its records are accurate and complete. After it became evident that some states weren’t reporting certain types of records, Congress passed the NICS Improvement Act of 2007.

While the law, as signed by President Bill Clinton (D), was named the “Brady Act,” the requirement that the background check be instant and that the records be destroyed actually originated with the NRA.

The temporary provision had one fatal defect. State and local law-enforcement officers don’t work for the feds, and don’t take orders from the federal government. Sheriff Jay Printz from Montana and other sheriffs from around the country, who were busy stopping crimes in progress and solving murders, refused to take orders from Washington, D.C., to search for records on their fellow citizens who were buying handguns—they did this despite an ATF spokesman’s threat that the sheriffs could be prosecuted for not doing so.

I was privileged to represent these sheriffs in several cases all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in Printz v. U.S. (1997), a 5-4 opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia, that Congress may not compel the states to administer a federal regulatory program. The Tenth Amendment prohibits Congress from giving orders to local law-enforcement officers to do its bidding.

In 1998, the permanent provision kicked in, under which the FBI would do the background checks themselves. The law provides that, if a person may lawfully receive a firearm, NICS shall assign a unique number, provide the number to the dealer and “destroy all records of the system with respect to the call” (other than the number and the date) and “all records of the system relating to the person or the transfer.” A no-brainer, right?

The bombshell hit when Janet Reno, Clinton’s attorney general, of Waco tragedy fame, announced that NICS was ready to go operational. Instead of destroying the records on lawful gun purchasers, NICS would retain the full information on the firearm purchaser—name, address, race and date of birth—for six months. She called the list an “audit log” rather than gun-owner registration.

It did not matter that the law provided that no federal agency (1) may “require that any record” generated by NICS “be recorded at or transferred to a facility owned, managed or controlled by the United States,” or (2) use NICS “to establish any system for the registration of firearms, firearm owners or firearm transactions,” except of ineligible persons.

I was privileged to litigate the issue in NICS v. Reno. But in 2000, in a 2-1 opinion, the D.C. Circuit upheld Reno’s regulation on the basis that it could not understand what the word “record” meant: “What is a ‘record,’ when has it been ‘recorded,’ and what kind of ‘record’ cannot be ‘recorded?’” The law, of course, couldn’t have been clearer. Further, the court said that registering gun owners for six months wasn’t a system of registration of gun owners.

Joining in the court’s decision was Judge Merrick Garland. You’ll recall that he was President Barack Obama’s nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court following Justice Scalia’s death. Imagine how lopsided the Court would have become had that nomination succeeded.

In dissent, Judge David Sentelle wrote that “the Attorney General is not only making such an unauthorized power grab, but is taking action expressly forbidden by Congress.” Her excuse was that Congress didn’t say when NICS had to destroy the records. Sentelle found that “reminiscent of a petulant child pulling her sister’s hair;” her mother tells her to stop, but she does it again, with the defense: “Mama, you didn’t say I had to stop right now.”

Finally, Congress had to step in and mandate that the records of approved gun purchasers must be destroyed within 24 hours of NICS approval of the sale.

Issues with the Data

In more recent years, the law governing NICS has been amended several times. Congress passed the NICS Improvement Act of 2007, which furnished states with financial assistance to encourage full reporting and to support the restoration of rights to persons who at some time had been committed to mental institutions but were fully recovered. (Before that, having a mental-health commitment meant a lifetime ban on gun ownership.)

In 2017, the Fix NICS Act was introduced to beef up the existing requirement that the agencies send the necessary reports to NICS. It seems incredible that heads of agencies had ignored the law and, instead of being fired, had to be threatened with losing bonus pay if they continued doing so. The bill also offered the states more grants to report records.

NICS also needed fixing in another regard. As I testified in a hearing in the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, sometimes NICS denies a gun purchase based on an incorrect record. If a person who is actually eligible to purchase a firearm appeals the denial, NICS puts the onus on that person to straighten out the record with the governmental unit that originated it. The person then might find that agency to be unresponsive and, so, will be stuck in this bureaucratic limbo. NICS should thus be required to contact the originating agency directly in order to correct such records.

Unfortunately, Fix NICS passed without such an amendment. Citizens should not be deprived of due process and Second Amendment rights because some government agency maintains incomplete and inaccurate records. The attorney general could promulgate a regulation to correct the problem.

In some cases, NICS has the ability to verify whether a record is inaccurate in a matter of minutes because many court records are now online. If a rejected gun buyer claims that a federal conviction record in the NICS system is inaccurate, a NICS examiner can access the judgment of conviction, if any, with a few clicks on the computer via PACER.

Defendants are frequently over-charged with more serious crimes but are found not guilty or guilty of less serious crimes that do not disqualify such persons from purchasing a gun. I once handled a NICS appeal in which my client was originally charged with a felony but was found guilty of a misdemeanor. NICS only found the felony charge and denied the purchase. In our appeal, NICS instructed us to have the U.S. marshal in the relevant court certify the correct record, but that office wouldn’t even answer our mail. I knew NICS counsel at the time, called her up, and she quickly found the correct record through PACER.

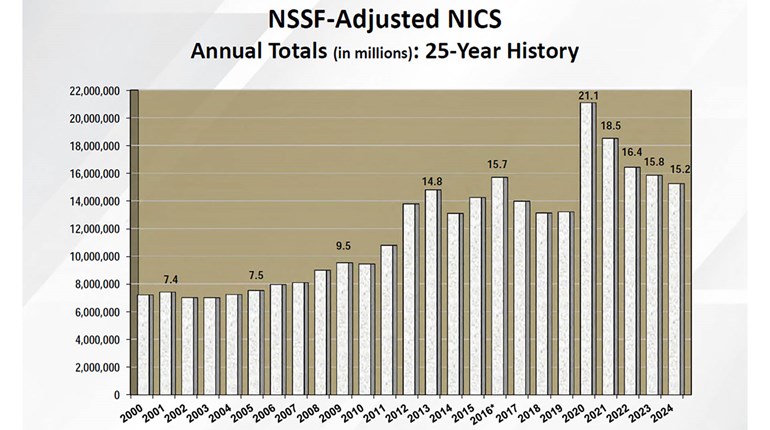

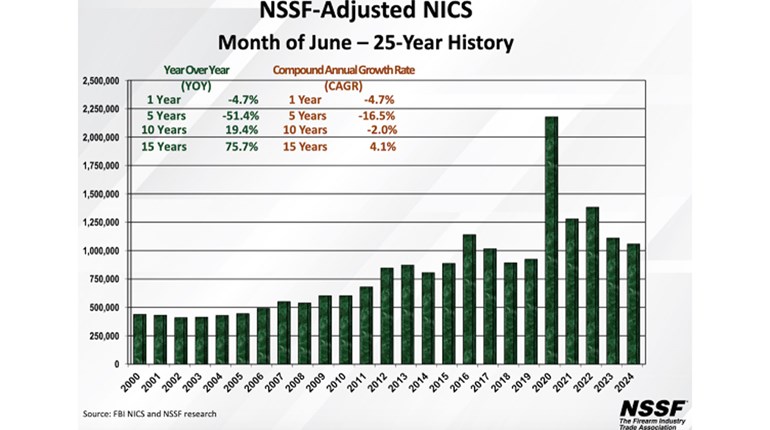

This is in no way intended to bash NICS, which generally runs smoothly and has many dedicated employees. This year, NICS has been working through the highest number of gun sales in American history (indeed, in world history). Sales began surging at the beginning of 2020 due to the war on gun owners advocated by the Democrat presidential contenders and carried out by new legislation, escalated because of the uncertainties of the coronavirus pandemic and skyrocketed even more in reaction to the riots, looting and arson throughout this summer.

Nonetheless, law-abiding gun owners must stay vigilant so the tool isn’t corrupted by anti-gun actors in the future. NICS must never be allowed to keep records on approved buyers. Gun registration means gun confiscation.

Stephen P. Halbrook, an attorney who has argued cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, is a senior fellow with the Independent Institute and author of The Founders’ Second Amendment, Gun Control in the Third Reich, and Gun Control in Nazi-Occupied France.