Partly cloudy skies greeted the residents of Oahu as they rose on Dec. 7, 1941, on what might otherwise have been another idyllic tropical Sunday. As the sun edged up out of the blue Pacific, it seems profoundly unlikely that any knew the scale of disaster that was winging its way from 230 miles north of the island.

Except, perhaps, for Takeo Yoshikawa.

Since April 1941, the former Imperial Japanese naval officer had been spying extensively on military installations around the island. Operating under a relatively weak “cover” identity as Tadashi Morimura, he lived on the grounds of the Japanese Consulate with a mission to simply observe the comings and goings of the Pacific Fleet at nearby Pearl Harbor. His good English, memorization of the outlines of U.S. Naval vessels and study of published U.S. Navy doctrine prepared him well for his clandestine observations.

Before long, his detailed communiqués on ship movements were flowing back to superiors in Japan. Despite traveling over “open” (commercial) radio channels and in a code already broken by Navy cryptographers, he would manage to lay the crucial groundwork for the devastating attack without arousing any suspicion. Yoshikawa doubtless did not know the actual date for the attack, and was arrested with other Consular staff the morning of the raid. He was repatriated to Japan in August 1942 under no suspicion as to his role.… [Yoshikawa] would manage to lay the crucial groundwork for the devastating attack without arousing any suspicion.

Yoshikawa/Morimura’s espionage remained undiscovered for many years after World War II, but the damage for which he helped set the stage was immediately and indelibly impressed on generations of Americans before the day was out.

The scale of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s assault force may be a difficult to appreciate. The Imperial Japanese Navy sent 60 percent of its aircraft carrier force (the largest and best-equipped in the world by a good margin at the time)—a total of six “flat tops”—toward Oahu’s military installations. Even by today’s standards, this would constitute the second-largest carrier contingent afloat, and the aircraft the twelfth-largest combined air force (414 aircraft, of which 353 would actually be launched at U.S. installations) in the world. Two battleships, three cruisers, nine destroyers, 27 submarines (four “midget”) and eight tankers escorted the carriers to their attack position.

Two waves hit U.S. installations, the first arriving at 7:48 a.m. In a happy coincidence that would go on to affect the entire course of the Pacific war, the three American aircraft carriers—sister ships Lexington and Saratoga as well as Enterprise—were not in Pearl Harbor on the morning of the seventh. Saratoga was in San Diego, and the “Lady Lex” and “The Grey Ghost,” though in Hawaiian waters, were on exercises with their cruiser escorts. The IJN aerial armada was thus deprived of their top two priorities.

This left the battleships of “Battleship Row,” anchored just off the harbor’s central Ford Island. On that day, eight were anchored in Pearl’s shallow waters. All would be hit, with five sunk or deliberately run aground to prevent their foundering. A total of 18 vessels from the battlewagons on down to cruisers, destroyers and support ships were damaged. More than half the fatalities of the day occurred aboard Arizona when her forward ammunition magazine detonated. She sank with 1,178 aboard.

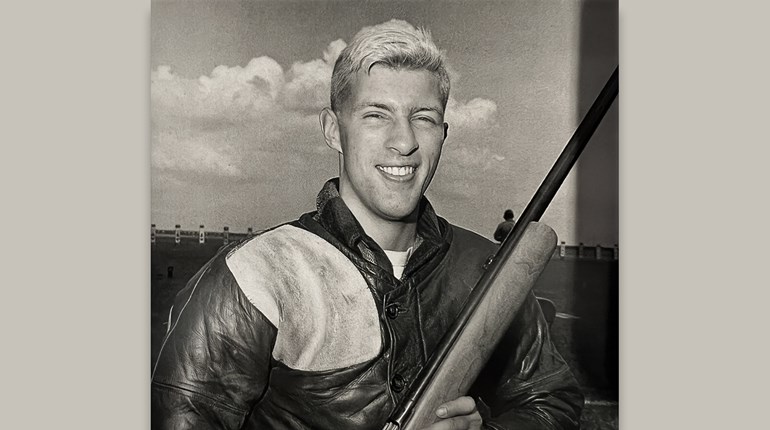

For nearly two hours, the IJN had things mostly, horribly their way. In addition to ships, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed outright, and another 159 damaged, nearly all on the ground; barely 50 were unscathed by day’s end. At least 14 U.S. pilots managed to take off and engage the enemy in the air. Six Army Air Corps pilots scored one or more “kills” against the attackers, among them Second Lieutenants George Welsh and Ken Taylor. The two had been up most of the night when the attack started, and went aloft in their “mess dress” without waiting for orders.More than half the fatalities of the day occurred aboard Arizona when her forward ammunition magazine detonated.

In the milieu, it remains unclear which of the pair scored the first air-to-air victory, and between them they may have downed as many as six despite 6-to-1 odds against them. Both survived the ensuing war and earned Distinguished Service Crosses for their heroism. Nor were they remotely alone: 15 Medals of Honor, 51 Navy Crosses, four Distinguished Service Crosses and 53 Silver Stars were among the many decorations awarded for heroism during the battle.

Despite a horribly lopsided tally by the battle’s end, Pearl Harbor defenders rallied as the second wave arrived. Only nine attackers were downed from the first wave, but 20 were lost in the second. This was among many factors that convinced Admiral Nagumo not to launch a third wave. He was widely criticized for this at the time, as un-attacked resources at Pearl Harbor proved instrumental in the next few months: Oil storage was left largely intact, as were the mammoth refitting and repair capacities. The carriers had already escaped, and all but two of the battleships would be raised; the former would fight to a draw in the Coral Sea in May, and then inflict a devastating defeat on Nagumo at Midway in June of 1942. His subsequent commands at Guadalcanal and Saipan would be gnawed by battleships (California and Tennessee) and cruisers (San Francisco) that escaped him at Pearl Harbor. Despite his triumph in December 1941, he would go on to take his own life in July 1944.

The story of the attack on Pearl Harbor has been told and retold in many dozens of books, films and articles, very much befitting the significance and complexity of both the era and the event. The modern penchant for a “short version” is difficult to justify for those same reasons: The attack was too costly and too important in the broader sweep of history not to take the time for fuller knowledge, and at least partial understanding.

Such understanding—and appreciation—seems even more necessary as the very last survivors of that fateful day seventy-five years ago pass forever into history. Find one, if you can: It is not too late to say, “Thank you.”Only nine attackers were downed from the first wave, but 20 were lost in the second.

Editor’s Note: Though we deride the short version, we’re the first to concede that “short” is considerably better than “none.” In this spirit, we’d steer you away from 2001’s historical, ensemble cast, epic-wannabe film “Pearl Harbor” without a strong proviso. Certainly well-intentioned, and with impressive flying/fighting CGI for the period, the broad strokes are at least correct, though details and the connection to the Doolittle Raid of April 1942 are sketchy to say the least. The best scenes are probably those that try to capture the Welch/Taylor defense of various airfields, but Taylor himself described the adaptation as “… a piece of trash … over-sensationalized and distorted.”

“Tora! Tora! Tora!” (1970) is considerably better. Meticulously researched and elaborately staged, with considerable authentic flying footage, it shows historically accurate detail on both sides of the engagement. (Eventual) USAF Brigadier General Kenneth Taylor consulted on the making of the film.

We asked noted aviation historian and friend of American Warrior/A1F Daily Barrett Tillman for his observations, and he concurred about “Tora! Tora Tora!” However, he noted that “From Here To Eternity” (1953) has merit too; whether despite or because of Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr’s beach scene, he was less specific. For the reader, he recommends Day of Infamy, by Walter Lord. “It’s been overtaken to some extent by decades of research, but holds up well on the personal level with good descriptions,” he said. At Dawn We Slept (Prange/Goldstein) is a longer and more detailed treatment, but suffers somewhat from a lack of underlying knowledge about naval aviation.