Let us say at the outset: Within the bounds of safety, feel free to shoot at anything you like and are willing to clean up. But—and you knew there would be one—don’t delude yourself into thinking that just anything will help you build your skills, especially if you don’t use it correctly.

A couple of “to-do” items kick us off. Whether indoors or out, make sure your target is a safe one. This has two interpretations. The first is really obvious: Can the material of which your target is made be safely struck by projectiles moving at many hundreds to several thousands of feet per second? This almost always means, “Is it readily penetrable so the bullet trap/backstop can do its job?” As we alluded, this may seem a major “duh,” but a target that can redirect bullets is dangerous in the extreme depending on range design, and whether you are indoors or out. Urban gunnies will likely have this moderated for them by range staff, though it’s important to remember that it is still your responsibility; they’re just the safety net. Always inquire before you, ahem, improvise. So what to buy, in quantity or otherwise? You don’t need a huge variety. Chosen wisely, three will easily suffice in our view.

Mostly, this will mean the logical choice is paper, and the second consideration is therefore corollary—“consumable” support that abides by the same rules: penetrable, and not the sort of material that throws bullets back at you or directs them off the range or outside your backstop.

Once over the safety hurdle, “don’ts” are somewhat more subjective, though more to our point. Depending on what you’re trying to accomplish, target selection can be a disproportionate benefit or hindrance, and which isn’t always obvious. In no particular order:

Ad Hoc Targets

This Latin phrase literally translates as “for this,” but is often and slightly misused in modern argot. Clarity counts for our purposes, however, as you’ll see: Rather than the correct “arranged for a particular purpose,” it has come to be interpreted as “improvised.”

Fair enough, at least to make our point: Ad hoc targets have value in an “it was all I had” circumstance, and are certainly preferable to picking out just any old smallish, farish thing to pelt with gunfire. They’re more likely to be legal, too, but their (often severe) limits should be understood. Take a look at our headline image, for instance: This might work to check zero in an emergency, but it’s a bad idea for lots of reasons. First, this damn well better be your fence. Second, what do you think the merest puff of breeze will do to this target? Third, good luck with that aiming point. Fourth, can you imagine trying to establish a (not check an existing) zero on this? Fifth (and in some ways what worries us most about the mindset that improvising engenders), what do you think of the backstop? Granted, the photo makes it unclear, but explaining it—hit or miss—to a landowner or local sheriff gives us some major willies.

Does this mean we never use them? Heck no. But the point is that you have to keep the purpose of your shot in mind in target selection. On an unshot backing, for instance, small paper plates at intermediate distances are great for transition practice with pistols, carbines and rifles, and can often be used in “lane-only” venues where this is otherwise hard to train. At longer distances, we understand the appeal too, though keep in mind it’s a highly unrealistic target in terms of contrast—especially for rifle work.

The big knock on ad hoc targets is how little they generally tell you about non-hits. Despite the fact that they are easy and inexpensive, most variations are poor on this score, and only very near misses are recorded at all. Choose even a little bit carefully and buy in numbers—you’ll almost certainly be better off.

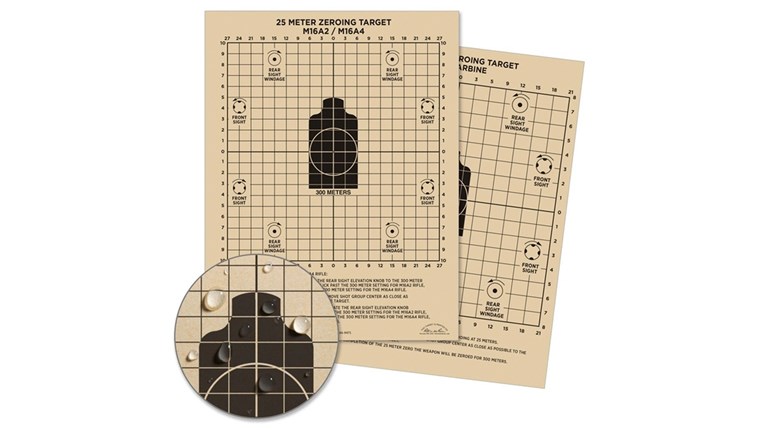

Printed Targets

So what to buy, in quantity or otherwise? You don’t need a huge variety. Chosen wisely, three will easily suffice in our view. While we don’t shoot at these a bunch anymore, we like to keep around what the NRA calls the TQ-7 “25-ft Rapid Fire Pistol Target.” One thousand of them cost $37.50 (or .0375 cents each), so we expect no squealing about imminent penury. Your range is almost certain to stock something very similar if you don’t want to store them. But don’t let that center get too big—the 1.5-inch actual bull is big enough. Use targets correctly. If you want a cause célèbre for today, this is actually it.

There are a couple of reasons these are a favorite. They stand in well for our confidence drill, for openers (though we still prefer the 1-inch square/dot, shot closer), if you don’t want to fabricate your own. Second, they are excellent for assessing any changes to the sight regulation on a handgun. Finally, they’re good old black-and-white. Colored “bulls” of any sort are easier to see, but therein lies their weakness: No real-world shooting problem is likely to visually conform to those easy-to-see color schemes. We concede that bull’s-eyes are rare, too, but the drabness of these puts the emphasis on a good sight picture. Last, perhaps, is that the low cost of these means you won’t—or at least shouldn’t—be tempted to over-shoot them. Twenty rounds is plenty—more hits become a visual distraction that adds no value (more on this later).

And all you pizza box guys: Here’s where they come into play. Use them as an unmarked “backer” to give smaller paper targets a little physical integrity. As a target in and of themselves, you’ll almost always shoot them too many times.

For tactical-style shooting, move to something else. It’s our considered opinion that the TQ-7 takes “aim small, miss small” to an unhelpful level (despite its “rapid fire” moniker). Defensive shooting is still about center mass, though this is pointedly not the same as pray-and-spray. (If this is your deal, please buy a can of pepper spray and choose a new hobby.) The goal of the second target type is useful precision, i.e., that which stops an attack. This is a particular favorite: In long use at Gunsite Academy, it’s a silhouette of useful scale and shape, and “randomized” so that rapidly choosing a particular visual cue is mostly defeated—it will effectively make you adopt good framing of the sight for defensive encounters. This is reinforced by critical hit areas being subtly outlined—little or no help when you’re pulling the trigger, but also no fooling yourself when you repair the target.

The last printed type you should stock is also a silhouette, namely, photorealistic. (This one, designed by friend of A1F and former U.S. Navy SEAL Jeff Gonzales, is a favorite.) These are politically unpopular to be sure, but necessary: They confound an iffy technique sight picture like nothing else. If you’re still letting the eyes race out and back rather than focusing on the front sight, you’ll see performance times on virtually any drill climb.

Use Targets Correctly

If you want a cause célèbre for today, this is actually it. In general terms, we hope what we’re about to say will now be a no-brainer.

Bull’s-eyes are not great for tactical shooting, but tactical targets won’t help you winnow out technique flaws. To develop a proper, complete shot—presentation, sight picture, trigger press and follow-through—“bulls” are good. Lest we become too doctrinaire—and, frankly, it’s a problem in shooting in general—these are recommendations, not a fifth Gospel.

Tactical targets (both silhouettes) aren’t good for precise shot development, though this doesn’t mean you won’t practice precise shots on them. “Failure to stop” drills/shots must be practiced here.

Don’t let any of these targets become a visual acuity exercise. Though it’s OK for it to be fuzzy in outline (such is an optical reality and how human vision works), if you can’t see your target clearly—if it’s a blob—you need a bigger aiming point.

Repair targets regularly. This is the single biggest error shooters make in our view. There is simply no way to improve beyond a certain basic level (especially with a pistol) if you can’t relate technique differences shot to shot with point of impact. If at all possible, repair targets with the proper materials: Masking tape is common and cheap, but you won’t see it used by most serious shooters, at least not in serious applications. This relates directly to our next point …

Replace targets regularly. A TQ-7 should only get 20 shots; either of our silhouettes no more than 50. There is just no escaping the effect “visual clutter” has on the brain and on later shots—distraction in the former, casualness in the latter. Neither are constructive, and are exacerbated by shabby repair.

Finally, put any paper target on a backer. If you’re outdoors, it’ll put an end to fluttering distraction. If inside, you’ll be sure you’re boring that hole in the center, and not spraying things around.

Many of these considerations apply to rifle targets, and we admit we’ve said little about this. Also, of course, there are targets that are both target and backer, and both have their place.

Lest we become too doctrinaire—and, frankly, it’s a problem in shooting in general—these are recommendations, not a fifth Gospel. Visual differences, among other things, may make some of our choices and preferences unhelpful, or even unworkable at the extremes. But the bedrock we don’t concede: Make sure you’re clear in your own mind what you’re trying to accomplish when you buy targets, don’t change just for the heck of it, and take every shot like it matters.

Because it does.