“How” World War I began is an oddly well-known historical episode—with the assassination of Austrian Imperial heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by a Serbian Nationalist. That the intended assassination attempt for that June day in Sarajevo had already failed is less well known. Only a peculiar chain of mischances gave Gavrilo Princip a second opportunity to strike the royal couple, and succeed where his six co-conspirators had not.

The “why” that followed was a typically Balkan convolution. Alliances formed and treaties unraveled all over Europe, with war becoming inevitable in late July. Between July 28 and Aug. 4, the sides were drawn up and hostilities declared: Germany and the Austria-Hungarian Empire (eventually joined by Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire) were the “Central Powers,” while France, the British Commonwealth, Belgium, Serbia and the Empire of Russia formed the encircling “Allied” nations (Montenegro, Romania, Greece, Portugal, Italy and the Empire of Japan would join somewhat later, followed by the United States in 1917). Conflagration writ very large soon followed.

The theaters of the war would expand rapidly along the colonial lines of the day, not just across 450 miles of the infamous “Western Front” in France and Belgium (as immortalized in E. M. Remarque’s 1928 “All Quiet on the Western Front”). Far-flung engagements raged, costing Germany most of its considerable pre-war colonial holdings in Africa and Southeast Asia. The British would extensively harass the Ottomans throughout much of the Middle East as chronicled by archeologist Thomas Edward Lawrence—eventual British Army Colonel and famed “Lawrence of Arabia.”

After the first few months of war, French and British Commonwealth casualties in Europe alone were over a million. The two Allied powers attempted a second front against the Ottomans to relieve the Western stalemate. Championed by First Sea Lord Winston Churchill, the attempt to break through the Dardanelles and into the Black Sea at Gallipoli would prove another ghastly stalemate—a half-million casualties (110,000 dead) on both sides—by the time it ended in January 1916. Churchill was his own harshest critic, resigning his cabinet post to join the Royal Scots Fusiliers in France as an infantry Major at the age of 41.The “war to end all wars” sadly wasn’t. WWI began 101 years ago this week.

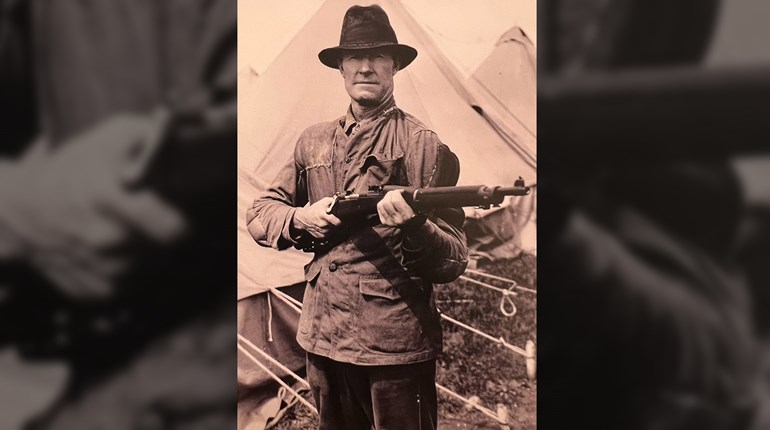

The trench warfare of the Western Front moved surprisingly little after initial German incursions of 1914. Unlike World War II, troops were not extensively mechanized, and trench-to-trench advances were often measured in distances of mere yards to a very few miles. Grinding diseased attrition mirrored the unsubtle tactics and weapons of the day: Massive artillery bombardments were followed by charges through “no man’s land,” typically a thicket of barbed wire, and overseen by German Maxim machine guns from the East, or British Vickers or Lewis machine guns from the West. Though temperamental by modern standards, all were devastating in the hands of experienced four- to six-man crews: During a British attack at the Somme in the summer of 1916, 10 Vickers guns fired 1 million rounds in a single 12-hour engagement.

Nor were crew-served machine guns the only examples of ferocious new technology: Tanks made their first appearance. Initial action with the British came at the Somme in September 1916. The materials and engineering of the day made them slow (walking speed) and prone to mechanical failure, but they proved formidable all the same, grinding through barbed wire and able to cross trenches up to nine feet wide. Small arms and machine gun fire left them largely untouched. Mostly due to small numbers, they were not to have a great effect on the prosecution of the war. Large tank-on-tank engagements would have to wait for World War II.

Chemical weapons in the form of irritant or poisonous gases were also fielded by both the Central and Allied powers. French and German troops deployed irritant types to little effect in 1914, but the first reliable killing agent—chlorine—was used by the Germans on a large scale at Ypres in April 1915. The Germans deployed suffocating phosgene gas against Russian troops on the Eastern front that May. Often mixed with chlorine, phosgene would claim 85 percent of all gas fatalities during the war.

1917 saw the introduction of mustard gas, again at Ypres. A powerful blistering agent, it was less inclined than phosgene to kill outright, but it overburdened care capacity of field hospitals rapidly, and those exposed to it took many weeks to heal, or to die. The Germans led in gas technology for most of the war, but the Allies had superior protective gear. Mainly, gas became a psychological weapon, though a dangerous one: Shifting winds can and did blow gas attacks back on their initiators.After the first few months of war, French and British Commonwealth casualties in Europe alone were over a million. The two Allied powers attempted a second front against the Ottomans to relieve the Western stalemate.

Aircraft of rapidly evolving types also appeared. Employed for observation of enemy troop movements early on, virtually every modern use of airplanes in warfare was at least explored. Engine power and structural material strength limited bomb loads for strategic or tactical bombing, yet lighter-than-air craft (the famous Zeppelins) and heavier-than-air craft like the Gotha G and Zeppelin Staaken all bombed England. Observation missions eventually became shooting affairs, with the aim to deny intelligence about troop and matériel movements. The red Fokker triplane of Manfred von Richthofen (Germany, 80 victories), the Nieuport of Billy Bishop (Canada/RAF, 72 victories) or the Spad of Eddie Rickenbacker (U.S., 26 victories) would soon be known the world over. The British even floated an aircraft carrier, HMS Furious, attacking the Zeppelin base at Tonder, Denmark, in July 1918.

Other sea-faring action was pervasive during the course of the war. The Kaiserliche Marine’s High Seas Fleet fought the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet to a tactical draw at the Battle of Jutland (off Denmark), while losing fewer sailors and ships in one of the largest steel battleship engagements every joined. Strategically, however, the battle was a British victory. The Germans were unable to break into the Atlantic to harass Allied ports or shipping.

More successful were German U-boats: While 199 were lost to various causes, they sank 5,000 Allied vessels. “Convoy” tactics and primitive sonar were reducing their effectiveness by late 1916, and they changed to unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917. The German goal was to strangle Allied supplies from the United States so that the British and French would sue for peace, and before sufficient American troops could arrive to turn the tide on the Western Front.

This change in U-boat tactics was the first of two provocations that brought the U.S. into World War I. The second was the so-called “Zimmermann Telegram,” which instructed the German Ambassador to offer financial support and the recovery of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona in return for Mexico’s entry into the war on the side of the Central powers. Despite poor relations with its northern neighbor, Mexico saw no way to engage the much more powerful U.S. and win, and doubted the reliability of German funding if they tried.

Even without a threat from the south, the United States declared war as an “Associated Power” on April 6, 1917.

The German U-boat stratagem was at least partly successful: Submarines sank a half million tons or more of Allied shipping per month through July 1917. Still, the German high command knew that time was a vanishing commodity and devised a daring, last-ditch plan. In March of 1918, remaining German troops abandoned mass artillery bombardment and troop movements in favor of smaller actions against multiple Allied weak points. Coupled with long-range bombardment by massive railway guns, the “Spring Offensive” advanced 37 miles (to within 75 miles of Paris) in a matter of days. But long supply lines and badly deteriorated logistical support in Germany would be their undoing as much as the 10,000 American troops per day who were now pouring into France.Even without a threat from the south, the United States declared war as an “Associated Power” on April 6, 1917.

By late September, Central forces were falling back to Germany or retreating in Italy. By November, Imperial Germany and Austria-Hungary were dead.

The end of World War I was arguably more complex than the beginning. While Armistices occurred on Nov. 3 (Austria-Hungary) and 11 (Germany), another seven months would elapse before the actual Treaty of Versailles. Ratification of various elements of the treaty and inclusion of other parties to the war would not end until 1923 (with another Treaty at Lausanne, Switzerland). All fronts and all combatants had a combined 15 to 18 million dead. That the number is not actually known is testimony of a singular kind.

In the ashes and among the graves lay four Empires, and not all Central powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman and Russia (overthrown in the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917). From the ashes rose nine new (or reconstituted) nations: Yugoslavia, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

There too, in the resentful wreck that was Germany in the wake of Versailles, a decorated Austrian Corporal lingered. Nursing grudges and deceits into megalomania, he would not need a second chance at a weak plan like Gavrilo Princip. In half a generation, he would make “The Great War” seem a pale harbinger. He would re-write the grisly tally of “the war to end all wars” into every sort of insignificance.

He was Adolf Hitler.